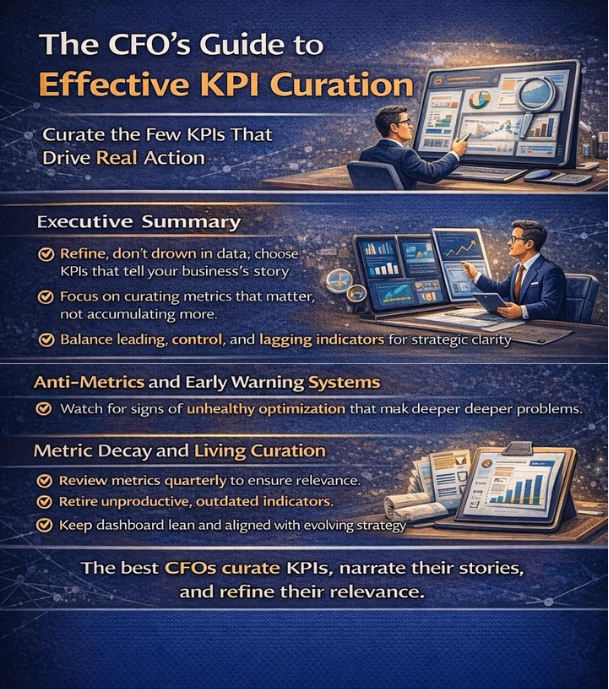

Executive Summary

In a well-run company, key metrics should tell a clear story. They should pulse like a heart monitor, not merely recording activity but signaling health. Yet walk into any operating review or board meeting, and you find yourself drowning in dashboards, trending arrows, heat maps, and color-coded indicators. The modern CFO does not suffer from a lack of data but from an overabundance of it. The real challenge is not generating more numbers but having the discipline to choose fewer ones that matter, tell the truth, and drive action. The best finance leaders are not scorekeepers but story curators. They know that metrics are not just there to measure performance but to shape it. People respond to what is tracked. Teams compete to improve what is visible. What gets measured gets managed, but only if what is measured is meaningful. Throughout my twenty-five years leading finance across cybersecurity, SaaS, manufacturing, logistics, and gaming, I have learned that the real risk is confusing the ease of measurement with the importance of the thing being measured. Just because something can be counted does not mean it has consequence. When I built enterprise KPI frameworks using MicroStrategy, Domo, and Power BI, the challenge was not capturing more data but extracting the few signals that matter from the noise. The CFO’s job is to be the Chief Editor of Metrics, not to flood the organization with data but to curate the indicators that drive action.

The Foundation: What Is the Business Solving For?

That work begins with an essential question: what is the business solving for? If that question is unclear, the metrics will always be muddled. A company solving for speed needs different indicators than one optimizing for quality. A business focused on customer trust cannot rely solely on short-term revenue per representative. A company trying to build long-term embeddedness cannot simply chase top-of-funnel metrics. The CFO’s job is to help the business get honest about goals and then identify the metrics that reflect whether those goals are being achieved on a leading basis, not just a lagging one.

Three Layers of Metrics

A useful framework separates metrics into three layers. Directional metrics are leading indicators that shape strategic movement. They are often behavioral including product adoption curves, usage intensity, retention cohorts, sales velocity, and time to onboarding. They do not prove success but suggest its trajectory. Control metrics are operational checkpoints including gross margin, working capital turns, and headcount productivity. They help assess whether the machine is operating within expected tolerances. Outcome metrics are the final measures including net revenue, cash flow, and profitability. They are necessary but by definition lagging.

| Metric Layer | Purpose | Examples | Business Phase |

| Directional | Leading indicators of strategic movement | Product adoption rate, usage intensity, retention cohorts, sales velocity, time to onboard | Pre-PMF and growth stage |

| Control | Operational health checkpoints | Gross margin, working capital turns, headcount productivity, CAC efficiency | All stages |

| Outcome | Final performance measures | Net revenue, cash flow, profitability, ARR growth | All stages (weighted higher at maturity) |

When I built KPI frameworks tracking bookings, utilization, backlog, annual recurring revenue, pipeline health, customer margin, and retention at a cybersecurity firm, we organized them by these three layers. Directional metrics gave us early warning signals. Control metrics ensured operational discipline. Outcome metrics confirmed results. Great CFOs work across all three levels but do not treat them as equal. They weight them by business context and adjust them as the business evolves. A pre-product-market fit company should obsess over customer feedback velocity and churn. A Series C SaaS company should be closely watching customer acquisition cost payback and expansion efficiency. A mature business with solid recurring revenue might care more about operating leverage and free cash flow conversion.

Curation Over Accumulation

Too often, we find the same stale indicators recycled from company to company including bookings, pipeline coverage, net revenue retention, burn multiple, and contribution margin. These are all useful if they are curated. But when everything is tracked, nothing stands out. When ten metrics light up red, no one knows where to look. And when indicators become wallpaper, they lose their bite. This is where a strategic CFO must draw the line. Choose no more than ten indicators that sit at the top of the house, ones that can be clearly explained, owned by functions, and tied to incentive design. They should be aligned with strategy, influenceable by action, measurable with consistency, communicated frequently, and tracked with discipline.

More importantly, each indicator should have a defined relationship to a strategic question. Not a number for its own sake, but an answer to something that matters. Are we monetizing efficiently? Look at customer acquisition cost payback, not just top-line growth. Are we delighting customers? Use net promoter score paired with renewal velocity and support resolution times. Are we building a durable revenue base? Net revenue retention and gross revenue retention must be decoupled and studied independently. Are we allocating capital with rigor? Look at return on investment on growth projects, not just spend levels but return curves.

When I rebuilt GAAP and IFRS financials for a high-growth SaaS company and designed cohort analysis frameworks, we paired traditional revenue metrics with behavioral indicators that predicted churn and expansion months before they hit the income statement. We tracked not just monthly recurring revenue but the velocity of expansion within cohorts, the time from initial purchase to first upsell, and the correlation between product usage patterns and renewal rates. These directional metrics allowed us to intervene proactively rather than react to lagging results.

Even more powerful is when the CFO creates metric narratives, a brief weekly or monthly insight that weaves numbers into meaning. Not just annual recurring revenue grew 8 percent, but expansion slowed in the enterprise segment while small and medium business drove net new logos, suggesting product-led motion is gaining traction but upsell sequencing needs review. That is not reporting. That is interpretation. That is leadership. At a digital marketing company where we scaled revenue from $9 million to $180 million, these narrative insights became a critical tool for aligning cross-functional teams around what the numbers were telling us about market dynamics, competitive positioning, and operational effectiveness.

Anti-Metrics and Early Warning Systems

One trick I have found invaluable is tracking anti-metrics, signals that suggest unhealthy optimization. Things like sudden dips in discount rate without corresponding revenue improvement, sales quota attainment masking deteriorating deal quality, headcount growth with flat productivity, and high net promoter score paired with rising churn suggesting politeness and not passion. These are canaries in the coal mine. They warn when the system is gaming itself. When I managed global finance for a $120 million logistics organization, we discovered that on-time delivery metrics were improving while customer satisfaction was declining. Investigation revealed that drivers were marking deliveries complete at the facility rather than at the customer location. The metric was being gamed, and the anti-metric of diverging satisfaction scores revealed the problem.

Board Communication and Strategic Coherence

What about metrics in boardrooms? Many CFOs feel pressure to present a dazzling array of metrics to impress investors. Resist that instinct. Boards do not want more numbers. They want fewer that matter. They want to see the strategic flywheel and how you are measuring its rotation. Throughout my work leading board reporting at companies including a gaming enterprise where I oversaw $100 million in acquisitions, the most effective presentations focused on five to seven core metrics that told a unified story.

I remember one board review where we presented 72 metrics in a packet. The board stopped after page ten. Not because they were lazy but because the key issues were already clear. Growth was slowing. Churn had crept up. Margins had dipped. The board wanted to understand why, not sift through vanity metrics. The CFO who can narrate these core metrics with strategic coherence earns trust far faster than one who dazzles with metrics that do not tell a unified story. When I secured $40 million in Series B funding at a nonprofit organization, the investor presentation focused on three directional metrics, two control metrics, and two outcome metrics. That clarity accelerated decision making and built confidence.

Metric Decay and Living Curation

Lastly, there is one measure every CFO should track, though it rarely shows up in a dashboard: metric decay. That is, how often do your indicators need to change? Are you measuring what mattered last year or what matters now? Do your current metrics reflect this phase of the market, this phase of your company, this customer behavior? Or are you chasing ghosts of relevance? When I improved month-end close from 17 days to under six days at a cybersecurity firm, we eliminated 40 percent of the metrics we had been tracking because they no longer drove decisions. They were artifacts of a previous operating model.

The best curation is living. Not ad hoc, but not static. It is reviewed quarterly. It is aligned with executive incentives. It is embedded into objectives and key results. And when a metric stops being predictive or actionable, it is retired gracefully and publicly. At the logistics organization, we held quarterly metric review sessions where each functional leader had to defend why their top three metrics still mattered. If they could not articulate how a metric drove decisions, it was retired. This discipline kept our dashboard lean and relevant.

Conclusion

As you think about curating indicators, remember you are not trying to build a prettier dashboard. You are trying to create strategic alignment. Your job is not to measure everything. It is to shine a spotlight on what really matters so that when the pressure comes, the business knows what levers to pull and what stories to trust. In a world flooded with metrics, the rarest and most valuable act is curation. That is the CFO’s opportunity: not to count more things but to count the right things and to turn that clarity into conviction.

Disclaimer: This blog is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax advisor or counsel for advice tailored to your specific situation.

Hindol Datta is a seasoned finance executive with over 25 years of leadership experience across SaaS, cybersecurity, logistics, and digital marketing industries. He has served as CFO and VP of Finance in both public and private companies, leading $120M+ in fundraising and $150M+ in M&A transactions while driving predictive analytics and ERP transformations. Known for blending strategic foresight with operational discipline, he builds high-performing global finance organizations that enable scalable growth and data-driven decision-making.

AI-assisted insights, supplemented by 25 years of finance leadership experience.