Executive Summary

The beginning of every startup feels like a lightning strike. There is urgency in the air, a kinetic energy that transcends business plans and pitch decks. The founding team sits elbow-to-elbow, answering customer support emails between investor calls and writing code while rewriting the pricing page. Every conversation is a decision. Every decision is a pivot. Throughout my twenty-five years leading finance across cybersecurity, SaaS, manufacturing, logistics, and gaming, I have learned that this fluidity feels like product-market fit in motion. And for a brief moment, it is. But what masquerades as momentum is often chaos tamed by proximity. Startups, especially in their first year, operate not with process but with presence. The co-founders have perfect visibility because they are in the room. And that works until it does not.

The First Year Illusion

The illusion of the first year is that what feels agile is actually fragile. The moment the company hires its first thirty people, the startup begins to bend under the weight of its own success. Decisions take longer. Execution wobbles. Customers feel it first in missed deadlines, erratic communication, and inconsistent product updates.

This is the moment when many startups begin to fail not because the product is wrong but because the operating model has not changed. Founders often mistake early-stage improvisation for strategic agility. But the tools that get you to your first million in revenue are often the same tools that hold you back from your tenth.

Key Symptoms of Outgrown Operating Models:

- Decisions taking exponentially longer as headcount grows

- Execution wobbling despite increased resources

- Customer experience degrading through inconsistency

- Founders becoming bottlenecks rather than accelerators

- Teams reverting to heroism rather than systems

The first lesson of scale is not about speed or capital. It is about rhythm. And rhythm requires structure. Operating models are not bureaucratic tools meant to slow down creativity. They are instruments of continuity. They are what allow judgment to scale even when people are no longer in the same room.

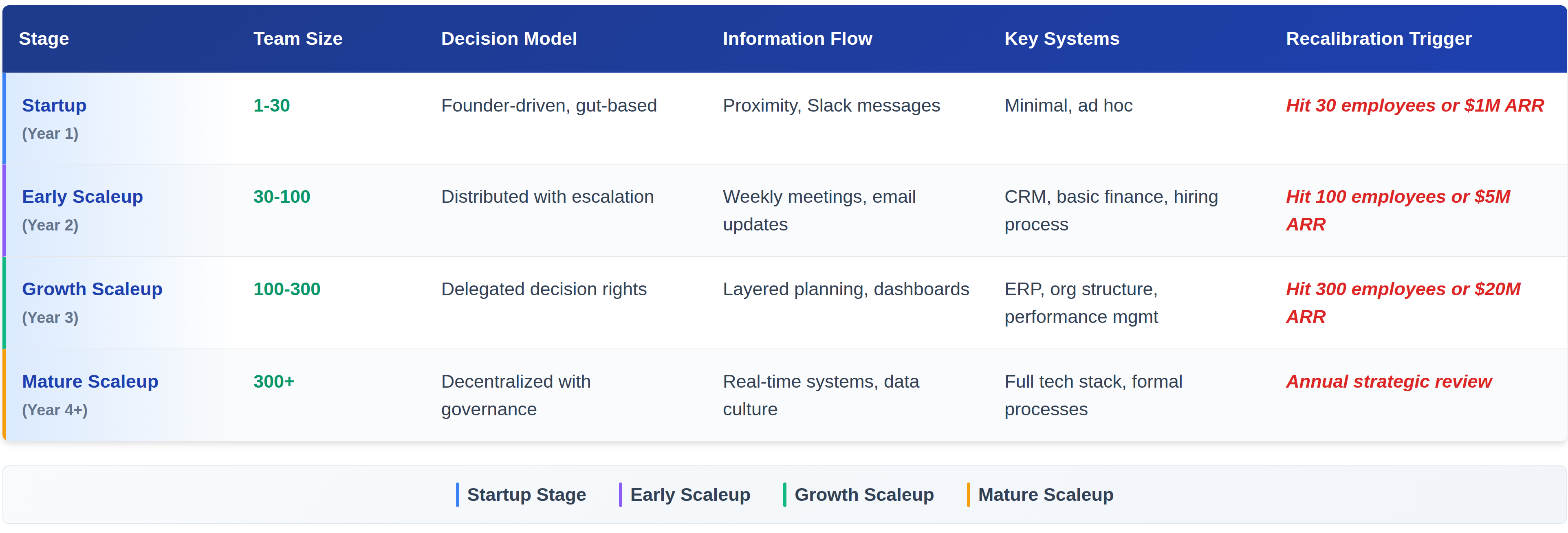

Operating Model Evolution Framework

Building While Running: Operational Recalibration

Every startup that survives its first twelve months faces a paradox: how do you build the airplane while flying it, especially when the wind speed is increasing? The companies that scale best are not those that have perfect operating models but those that treat their operating model as a living system.

Recalibrating the operating model begins with acknowledging that what worked last year probably will not work next year. The recalibration process starts with clarity. A strong operating model defines how decisions are made, how information flows, and how people are held accountable.

Core Recalibration Questions:

- What are the feedback loops, and are they still functioning?

- Where are the bottlenecks slowing execution?

- Which rituals (weekly reviews, sprint retrospectives, hiring loops) still serve their purpose?

- Which processes have become rote rather than value-adding?

- Where do decision rights need redistribution?

When I managed global finance for a $120 million logistics organization growing from 800 to 1,200 employees over 18 months, we conducted quarterly operating model reviews. At 900 employees, our centralized approval process for capital expenditures over $10,000 created three-week delays for regional operational investments. We redesigned decision rights, delegating approval authority up to $50,000 to regional directors with monthly oversight reviews. This reduced approval time from 18 days to three days while maintaining financial controls, accelerating critical operational improvements by five months and improving customer service metrics by 12 percent.

Operating Models as Moral Contracts

A company’s operating model is not just a system. It is a mirror. It reflects the values of the leadership team, the assumptions embedded in decision-making, and the implicit promises made to employees and investors alike.

When operating models do not evolve, people begin to fracture:

- Middle managers become friction points absorbing chaos

- Employees who thrived in ambiguity now crave structure

- What felt like freedom begins to feel like abandonment

- Culture cannot be maintained by osmosis

The leadership team’s job is not to manage chaos but to translate scale into stability without sacrificing speed. That means building an operating model that serves as a moral contract, one that sets expectations clearly and enforces them consistently.

As companies grow, these tensions multiply. Compensation systems buckle. Org charts sprawl. Product development slows. At this point, culture must be embedded in operating rhythms: how planning is done, how resources are allocated, how feedback is delivered.

The Twelve-Month Recalibration Cadence

Twelve months. That is the cadence at which most fast-growing companies must revisit their operating model. Not because something is broken but because the business has changed. New customers, new markets, new team members all reshape the logic of execution. What worked for a team of 20 breaks at 50. What worked at 50 implodes at 150.

Great companies do not wait for pain. They treat the operating model as a living organism. They build a culture of annual review: every year re-examining how decisions get made, how feedback loops are structured, and how execution is coordinated.

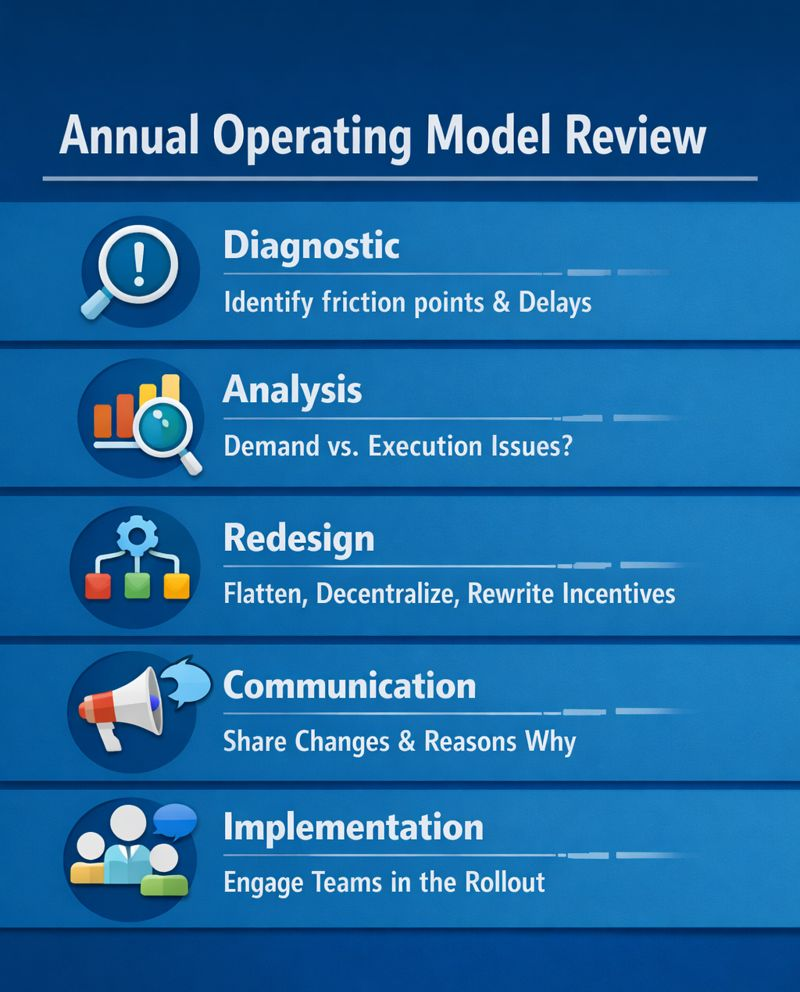

Annual Operating Model Review Process:

- Diagnostic – Where has growth created friction? Which decisions take too long?

- Analysis – Are issues demand-based or execution-based disguised as sales problems?

- Redesign – Flatten hierarchies, decentralize decisions, rewrite incentives

- Communication – Explain not just what is changing but why

- Implementation – Involve operators closest to the work in shaping new systems

When I improved month-end close from 17 days to under six days at a cybersecurity firm, the transformation required complete operating model redesign. We moved from sequential department-by-department close to parallel processing with real-time reconciliation. We redistributed decision rights for journal entry approvals, automated validation rules, and instituted daily rather than monthly review cadence. This was not a process tweak. It was an operating model evolution that required cultural change, system investment, and continuous refinement over three quarters.

My certifications as a CPA, CMA, and CIA provide technical foundation for operational design and continuous improvement. But what separates companies that scale durably from those that fracture under growth is not process sophistication alone. It is the discipline to diagnose operating model misalignment before crisis, the courage to redesign decision rights and information flows annually, and the wisdom to treat operating models as moral contracts that embed values into execution rhythm.

Conclusion

Twelve months is not a long time. But it is enough for a startup to evolve into a scaleup or to stumble into entropy. The companies that thrive are not the ones that have the best product or the deepest pockets. They are the ones that understand that scale is not a destination. It is a rhythm. And rhythm requires design that evolves every twelve months.

Disclaimer: This blog is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax advisor or counsel for advice tailored to your specific situation.

Hindol Datta is a seasoned finance executive with over 25 years of leadership experience across SaaS, cybersecurity, logistics, and digital marketing industries. He has served as CFO and VP of Finance in both public and private companies, leading $120M+ in fundraising and $150M+ in M&A transactions while driving predictive analytics and ERP transformations. Known for blending strategic foresight with operational discipline, he builds high-performing global finance organizations that enable scalable growth and data-driven decision-making.

AI-assisted insights, supplemented by 25 years of finance leadership experience.