Executive Summary

The cap table is not a spreadsheet. It is a blueprint. A quiet architecture of power, intention, and consequence. In the early days of a company, it is treated like a ledger, a record of who put in what and when. But as the company grows, that ledger begins to shape decision rights, strategic flexibility, and the lived experience of every stakeholder around the table. Throughout my twenty-five years leading finance across cybersecurity, SaaS, manufacturing, logistics, and gaming, I have learned that the mistake most companies make is managing the cap table like historians. Good CFOs treat it like architects. Architecture begins with vision. Not of what has happened but of what must be possible. A cap table must be designed backward from ambition. What kind of company are we building? How much capital will it require? How many rounds of financing are likely? What exit path do we anticipate including acquisition, IPO, or permanent private? These questions are not abstract. They are structural. They determine how much equity must be reserved, how much dilution is acceptable, and what kind of ownership shape must survive.

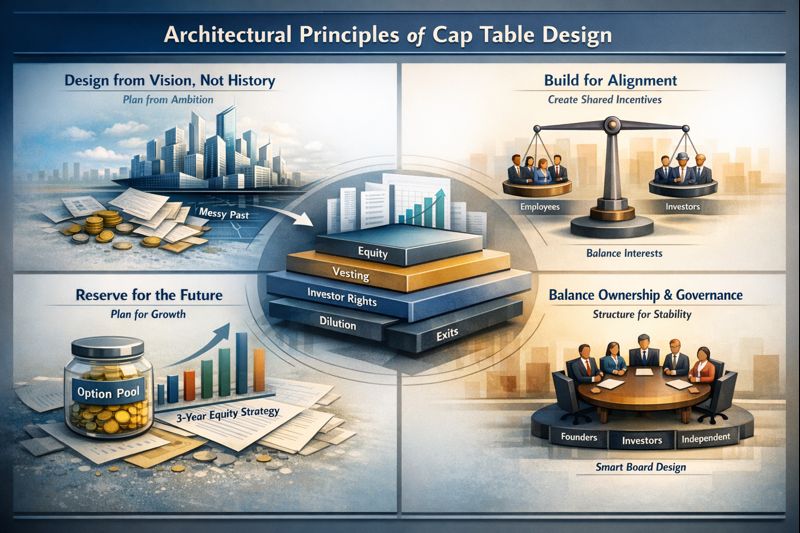

Architectural Principles of Cap Table Design

Principle 1: Design from Vision, Not History

Architecture begins with vision. A cap table must be designed backward from ambition. Most companies are born messy. Early friends-and-family rounds. Equity grants to advisors with vague scopes. Co-founders splitting shares emotionally rather than functionally. It feels generous at the time. Later, it becomes friction. CFOs who inherit these structures understand the quiet pain: a former advisor with 5 percent but no contact in years, a co-founder gone cold but still vesting, angels with pro rata rights but no alignment. These fragments create tension not just in boardrooms but in culture.

The work of architectural design is to anticipate these pressure points. It begins with clarity. Every grant, every clause, every vesting term must have purpose. Equity is not a gift. It is an instrument. It must match contribution, risk, and relevance. Founders who understand this early reserve equity for velocity, not sentiment.

Principle 2: Build for Alignment

The next principle is alignment. The cap table must reflect shared incentive. If early employees hold equity that vanishes in later rounds, morale erodes. If founders control too much without governance checks, investors balk. If investors accumulate rights disproportionate to support, strategy skews. The cap table must feel fair, not just numerically but narratively. It must tell a story everyone can believe.

This does not mean every stakeholder gets the same. It means every allocation makes sense. CFOs should model not just dilution paths but impact scenarios. What happens to ownership at Series B? At IPO? At a $200 million exit? At a $50 million one? These models shape hiring, fundraising, and retention. A cap table that only works in best-case exits is not a structure. It is a trap.

Principle 3: Reserve for the Future

Architecture is also about reserves. Too many companies under-allocate their option pools. They set 10 percent in early rounds and never revisit. Then, by Series C, they find themselves scraping equity to hire. Or worse, re-cutting grants in secondary markets. A smart CFO treats the option pool like a resource to be budgeted annually. Who needs equity? Why? How much? What will it drive?

When I managed equity compensation programs at multiple organizations, we maintained rolling three-year equity budgets modeling expected hiring needs by department and seniority level. At one SaaS company, we projected engineering headcount growth from 40 to 120 over three years and calculated option pool requirements for competitive grants at each level. We reserved 18 percent of fully-diluted shares, refreshing the pool at each funding round to maintain adequate reserves. This forward planning prevented last-minute scrambles and maintained grant consistency that supported retention.

Principle 4: Balance Ownership and Governance

Design extends to board construction. Ownership begets governance. A cap table that tilts toward one investor often leads to control imbalance. One that leaves founders too exposed invites pressure. A well-designed cap table anticipates how decisions will be made, not just who holds equity.

Cap Table Architecture Framework

| Design Element | Historian Approach | Architect Approach | Key Considerations |

| Equity Allocation | Reactive grants based on immediate need | Forward-looking reserves for 3-5 year roadmap | Option pool sizing: 15-20% fully-diluted at each round |

| Vesting Terms | Standard 4-year with 1-year cliff | Customized to role, risk, contribution timeline | Executive: performance vesting; Key hires: accelerated triggers |

| Investor Rights | Accept standard terms without negotiation | Balance pro rata, board seats, information rights | Align control with strategic value, not just capital |

| Founder Structure | Equal splits without role clarity | Weighted by contribution, risk, ongoing value | Include vesting for founders; revisit at milestones |

| Dilution Planning | React to each round in isolation | Model cumulative dilution across 5+ rounds | Target founder ownership: 15-25% at exit; employees: 10-15% |

| Exit Scenarios | Single path assumption | Model multiple exits: M&A, IPO, recapitalization | Waterfall analysis at $50M, $200M, $500M+ outcomes |

| Stakeholder Communication | Share cap table on request | Proactive quarterly updates with modeling | Explain how dilution creates value; show ownership evolution |

Living with Equity: Managing Evolution

The cap table is not a static record. It breathes. It evolves. It reacts to decisions made in moments of clarity, of panic, of ambition, of exhaustion. To live with equity is to live with compromise. No round is clean. No term sheet without friction. Every financing shifts ownership, compresses incentive, and alters the relative importance of players. The CFO must not only model these outcomes. They must narrate them. To boards. To teams. To founders themselves. The difference between dilution and damage is communication.

Managing Dilution Through Narrative

Start with dilution. It is the inevitable cost of growth. But how it is distributed matters. The CFO who slices equity mathematically without narrative loses trust. Equity is emotional. For a founder, 1 percent lost to a new investor may feel like betrayal. For an employee, a grant halved in the next round may feel like a vote of no confidence. These moments accumulate. And they shape culture.

Managing dilution is not about resisting change. It is about choosing the right tradeoffs. The right time to raise. The right mix of equity and debt. The right expectations set with every stakeholder. A CFO who can say you own less but what you own is worth more, and make that true, that is the difference between silence and revolt.

Evolving Incentives

Incentives must evolve too. The grant that thrilled a hire in Year Two may feel meager in Year Five. Option refreshes, accelerated vesting for key talent, and milestone-based awards are not luxuries. They are maintenance. CFOs must work closely with HR, with legal, and with department heads to ensure that equity still motivates. Because when it stops motivating, it becomes dead weight.

Navigating Transitions

And transitions complicate everything. A co-founder departs. An early executive wants liquidity. A team member leaves before vesting. Each of these events is a test of the cap table’s resilience. Buybacks, secondary sales, clawbacks, and extensions, none are easy. All carry ripple effects. The CFO must weigh cost against signal. What will this decision mean to those still here?

Living with equity also means navigating investor dynamics. Pro rata rights, super pro rata asks, and shadow ownership through SAFEs or warrants, each layer adds complexity. The CFO must manage expectations. Investors want more, always. But more for one means less for another. Strategic CFOs pre-wire these decisions. They create internal policies. They educate the board. They protect flexibility.

Preparing for Liquidity Events

Then there are the existential transitions. An acquisition. An IPO. A merger. Each turns equity into liquidity and in doing so reveals its true shape. Who gets what. When. How much. And under what terms. Liquidity preference stacks, unexercised options, expired ISOs, and RSU tax implications are not footnotes. They are outcomes.

A CFO unprepared for these moments creates chaos. Employees feel cheated. Founders feel blindsided. Investors grow hostile. But a CFO who has lived with equity consciously, who has audited the cap table quarterly, who has run exit scenarios and modeled waterfall distributions, this CFO brings clarity when it is needed most.

When I managed cap table evolution at organizations preparing for potential exits, we conducted quarterly waterfall analyses showing distribution at various exit values. At one company approaching acquisition discussions, we modeled outcomes at $75 million, $150 million, and $250 million valuations. This revealed that at lower valuations, liquidation preferences consumed most employee equity value. We used this analysis to negotiate founder secondary sales and employee option buybacks that created meaningful outcomes even in moderate exit scenarios, preserving morale and retention through the transaction process.

Continuous Stewardship

There is no perfect cap table. Only evolving ones. And evolution requires care. Equity should be re-underwritten each year. Do the grants make sense? Do the vesting terms still match commitment? Are reserves sufficient? Are rights aligned with performance? These are not tactical questions. They are structural.

To live with equity is to accept that fairness is perception as much as math. That ownership, once set, takes on a weight of its own. The best CFOs respect that weight. They build mechanisms to adjust. They bring transparency to complexity. They remind every stakeholder that equity is not a prize. It is a participation in building something enduring.

My certifications as a CPA, CMA, and CIA provide technical foundation for equity structure and valuation. But what separates architectural cap table design from historical record-keeping is not modeling sophistication alone. It is the vision to design backward from ambition, the discipline to reserve for future needs, the wisdom to balance ownership with governance, and the communication skill to narrate dilution as value creation rather than loss.

Conclusion

None of this is static. Companies change. People leave. Rounds evolve. But architecture, if thoughtful, absorbs this change without breaking. It provides the scaffolding. The goal is not symmetry. It is sustainability. A cap table that sustains hiring, fundraising, retention, and alignment through five to seven years of company life. That is not an accident. That is architecture. And the architect, unlike the historian, builds for what comes next.

Disclaimer: This blog is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax advisor or counsel for advice tailored to your specific situation.

Hindol Datta is a seasoned finance executive with over 25 years of leadership experience across SaaS, cybersecurity, logistics, and digital marketing industries. He has served as CFO and VP of Finance in both public and private companies, leading $120M+ in fundraising and $150M+ in M&A transactions while driving predictive analytics and ERP transformations. Known for blending strategic foresight with operational discipline, he builds high-performing global finance organizations that enable scalable growth and data-driven decision-making.

AI-assisted insights, supplemented by 25 years of finance leadership experience.