Executive Summary

A SPAC, or Special Purpose Acquisition Company, is a publicly traded shell corporation created for the sole purpose of acquiring a private company, thereby taking it public without going through the traditional IPO process. Think of it as a financial blank check company: it raises capital from public investors with no existing business operations, just the intent to merge with or acquire a private company within a set period, usually 18 to 24 months. Throughout my twenty-five years leading finance across cybersecurity, SaaS, manufacturing, logistics, and gaming, I have learned that liquidity events in business, like milestones in life, tend to come with equal parts promise and peril. And few financial instruments have surged and soured as dramatically in recent memory as the SPAC. Once heralded as a fast lane to public markets, the Special Purpose Acquisition Company has become, in the minds of many, both a shortcut and a cautionary tale. The basic concept is straightforward. A SPAC is a shell company that goes public with no operations, just capital and a management team. Its only purpose is to acquire a private company and take it public in the process. But as with most things in finance, the devil hides in the details.

How SPACs Work

A SPAC is typically formed by a group of experienced operators, former executives, or institutional investors, collectively referred to as sponsors. These sponsors often have expertise in a specific industry such as healthcare, fintech, or mobility and a track record of operational or investment success. The SPAC raises capital by going public through a traditional IPO. However, since it has no operating business, the disclosures are far simpler than a normal IPO. Investors purchase units, usually one share of common stock plus a fraction of a warrant to buy more stock later. The funds raised are placed into a trust account, earning interest and held solely for the purpose of acquiring a private target.

After the IPO, the SPAC has up to 24 months to identify and complete a merger or acquisition with a target private company. This merger, known as the De-SPAC transaction, effectively takes the private company public. Before the acquisition, SPAC shareholders vote to approve the transaction. If they do not like the deal, they can redeem their shares, typically at the IPO price plus accrued interest, significantly affecting how much capital remains for the target company post-transaction.

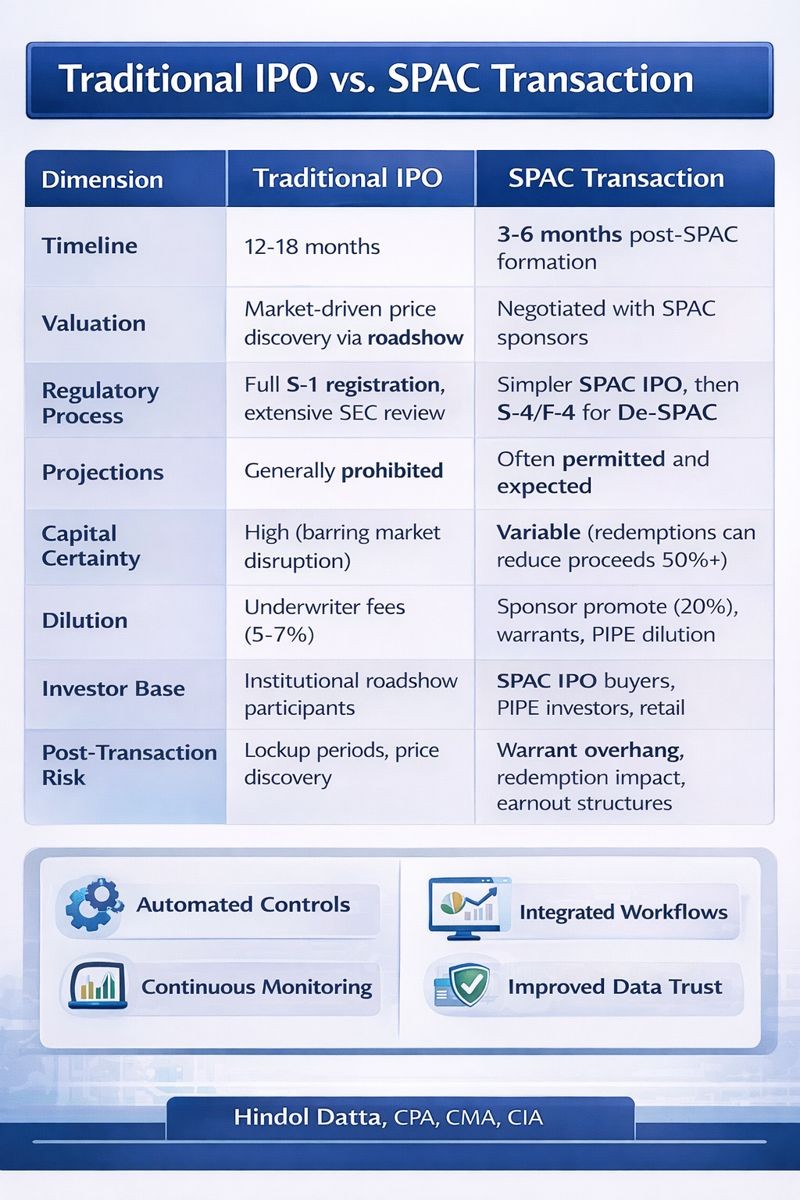

SPAC versus Traditional IPO

The Boom and the Bust

In 2020 and 2021, SPAC issuance hit record highs. Celebrities, financiers, and ex-operators all raised blank-check companies. De-SPAC transactions skyrocketed. Targets were often early-stage, capital-hungry, and short on financial maturity. In some cases, projections extended five to ten years out, with hockey-stick curves as far as the eye could see. But as interest rates rose and scrutiny returned, many SPAC-backed companies faltered. Their projections proved optimistic. Their financial controls proved thin. And the very promise of a shortcut to public markets became, in hindsight, an expensive detour. Redemptions soared. Share prices plunged. Investors, once giddy, turned skeptical.

So are SPACs dead? Not quite. But they are, like any financial instrument, only as good as the discipline behind them. The SPAC is a tool, not a magic wand. And for a CFO evaluating the path to liquidity, the question is not SPAC or not but are we truly ready for life as a public company, regardless of the route.

Critical Considerations for CFOs

A SPAC transaction, while faster than a traditional IPO, does not bypass the requirements of being a public company. You will still face quarterly reporting, SEC scrutiny, PCAOB-compliant audits, and investor relations demands. If your systems, controls, and leadership team are not already public-company caliber, the SPAC will expose that gap, often in front of a less forgiving audience.

When I improved month-end close from 17 days to under six days at a cybersecurity firm, we implemented automated variance analysis, exception reporting, and comprehensive audit trails. This level of operational discipline is table stakes for any public company, whether you arrive via traditional IPO or SPAC. More critically, the structure of a SPAC deal can be complex, sometimes to a fault. The sponsor economics, typically 20 percent of the SPAC’s equity, the use of PIPEs, the redemption mechanics, and the warrant overhang can make the post-transaction capitalization structure both dilutive and difficult to explain.

The CFO’s role in a SPAC process is not just to manage the numbers but to pressure-test the assumptions. What is the pro forma ownership? What happens if 80 percent of shareholders redeem? Are the warrants counted in diluted share count? How do earnout provisions align with realistic performance? And how does the capital structure look to future investors? In too many SPAC deals, these questions were not fully answered until it was too late.

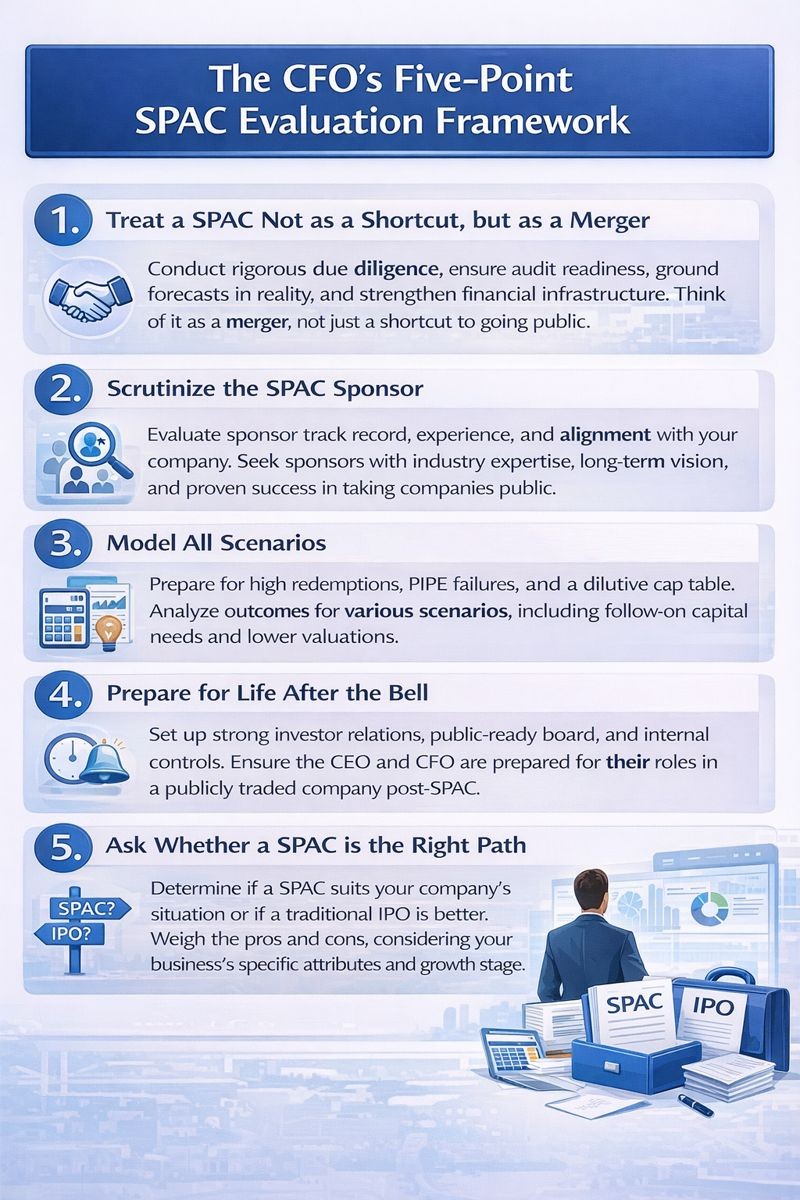

The CFO’s Five-Point SPAC Evaluation Framework

The Public Company Readiness Checklist

The CFO’s checklist must look the same regardless of the route:

- Can we close the books accurately and quickly?

- Are our forecasts credible and consistent?

- Is our board structured appropriately?

- Are we SOX-compliant or on the path?

- Can we manage investor expectations quarterly?

- Do we have investor relations, legal, audit, and tax resources in place?

- Is our valuation supported by fundamentals?

Capital markets, like nature, are efficient over time. They reward performance, punish opacity, and value consistency. Whether you enter through a SPAC or an S-1, the work required to stay public is the same. My certifications as a CPA, CMA, and CIA emphasize the technical rigor required for public company finance. But what separates successful public companies is not the route they took to get there. It is their readiness to operate with the discipline, transparency, and accountability the public markets demand.

Conclusion

A SPAC can be a tool, a potentially useful one. But it is not a strategy. And it is not an escape hatch. The companies that succeed post-SPAC are those that would have succeeded regardless. The route may be different, but the destination demands the same discipline. So is it SPAC-tacular? Sometimes. But more often than not, the better question is: Are we ready to be public? Because if the answer is no, no structure will save you. And if the answer is yes, any structure will do.

Disclaimer: This blog is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax advisor or counsel for advice tailored to your specific situation.

Hindol Datta is a seasoned finance executive with over 25 years of leadership experience across SaaS, cybersecurity, logistics, and digital marketing industries. He has served as CFO and VP of Finance in both public and private companies, leading $120M+ in fundraising and $150M+ in M&A transactions while driving predictive analytics and ERP transformations. Known for blending strategic foresight with operational discipline, he builds high-performing global finance organizations that enable scalable growth and data-driven decision-making.

AI-assisted insights, supplemented by 25 years of finance leadership experience.