Executive Summary

There is a special kind of quiet that fills a room when the cap table goes up on the screen. It is not the silence of confusion but the silence of consequence. Founders lean in. Investors watch closely. And operators, those who helped build the company from zero to now, hold their breath. Because unlike income statements or burn rates or net promoter scores, the cap table does not deal in potential. It deals in outcomes. Throughout my twenty-five years leading finance across cybersecurity, SaaS, manufacturing, logistics, and gaming, I have learned that the capitalization table is not just a record of who owns what. It is the living heartbeat of a company’s financial DNA. It tells you where power resides, how aligned incentives are, and what tomorrow’s headline will say if a term sheet turns into a transaction. Managing a cap table is not about spreadsheets. It is about stewardship. Because every decision that affects dilution, ownership, or incentive design changes the psychology of the people who build, fund, and eventually exit the business. Cap table management, done right, is part arithmetic, part game theory, and part long-range forecasting.

Dilution: Why Ownership Percentage Is the Wrong Question

Let us begin with dilution, the word that launches a thousand boardroom debates. Founders fear it. Investors monitor it. Operators misunderstand it. Dilution, in and of itself, is not bad. If you own 100 percent of a company worth nothing, you have 100 percent of nothing. But if you own 15 percent of a company worth a billion dollars, you are a millionaire many times over. The problem is not dilution per se. It is dilution without value creation.

Every time new capital enters a business, or new equity is issued to employees, dilution occurs. That is physics. But what matters is what that dilution buys you. Did it fund growth? Did it extend runway? Did it bring in world-class talent? Or did it just cover a shortfall in forecasting and a bloated burn rate? Good CFOs treat dilution like capital allocation. They ask is this equity we are giving up going to increase the pie enough to justify the smaller slice. They model not just ownership but exit scenarios. They align the timing of dilution with inflection points. Raising before you prove the next milestone often leads to punitive terms. Raising just after might mean a much better deal. It is timing, strategy, and narrative.

When I secured $40 million in Series B funding and an $8 million credit line at a nonprofit organization, we modeled dilution scenarios extensively. We analyzed how different valuation levels and option pool sizes would affect founder, employee, and investor ownership at various exit values. This transparency allowed the board to make informed decisions about timing, valuation expectations, and the trade-offs between dilution today and optionality tomorrow.

Equity as Incentive: Motivation Lives in the Details

Equity is not compensation.

It is belief.

Founders do not build companies for salary alone.

Early employees do not join startups for stability.

Investors do not take risk for modest returns.

The entire system works because people believe equity will turn into meaningful liquidity.

But belief erodes quickly when equity is poorly understood.

- Founders underestimate how post-round option pools affect ownership.

- Employees misunderstand strike prices, vesting, or tax implications.

- Investors negotiate protections that unintentionally choke future flexibility.

This is where the CFO’s role expands beyond math into narrative.

The best CFOs explain the cap table.

They teach people how equity works.

They make dilution understandable rather than mysterious.

When people understand their ownership, they behave like owners. When they don’t, misalignment quietly grows.

Retention is where this matters most. Equity can bind teams—or push them away.

- Cliff vesting that feels arbitrary can demotivate high performers.

- Late refresh grants can accelerate attrition.

- Overgenerous packages for late hires can poison morale.

Equity must be fair, contextual, and intentional.

At a digital marketing company where revenue scaled from $9M to $180M, we introduced structured refresh grants, clear equity education, and transparent exit modeling. The result was not just retention—it was trust.

Exits, Preferences, and the Reality of the Stack

Now, we must talk about the horizon, the exit. Because a cap table without an exit is just a ledger. The value of equity is realized when the company sells, goes public, or in rare cases creates enough profit to distribute dividends. And here, alignment becomes paramount. Founders want strategic exits. Investors may want faster ones. Operators may want liquidity along the way. Each party has different clocks. And the cap table sits at the intersection of those timelines.

Exit Scenario Analysis Framework

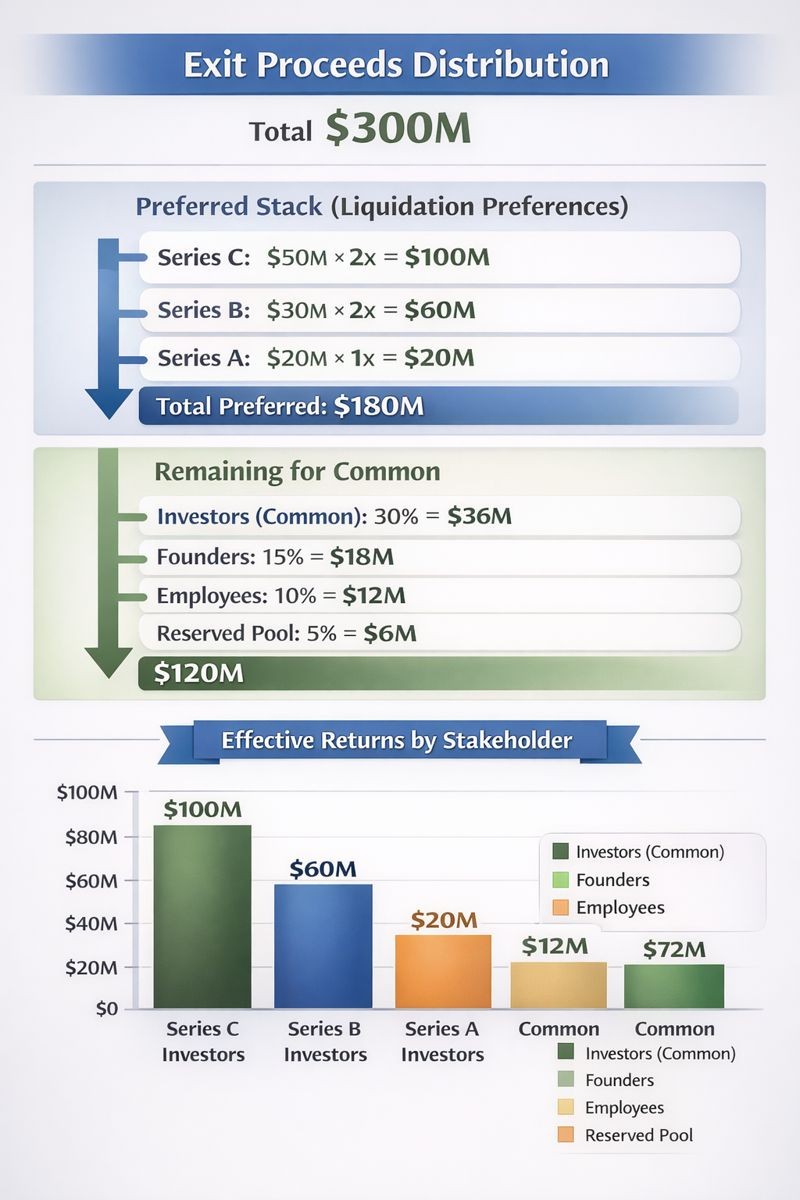

Scenario: $300M Acquisition Offer

This framework illustrates how liquidation preferences can dramatically impact distribution of proceeds. In this scenario, despite a $300M exit, preference stacks consume 60% of proceeds before common shareholders see any value. This demonstrates why preference terms must be modeled early and why founders and employees should understand how their equity value is affected by subsequent financing terms.

Consider a common scenario: a startup raises capital across five rounds. Early investors have 1x liquidation preferences. Later ones have 2x. The team has been diluted to 10 percent. The company receives a $300 million acquisition offer. Suddenly, preferences stack. The common shareholders get little. The operators feel shortchanged. Founders second-guess. The acquirers sense the discord. This is not just math. It is morale.

The lesson: cap tables must be actively managed with exit scenarios in mind. Preferences should be modeled early and often. Secondary sales must be considered not just as liquidity but as alignment tools. And perhaps most importantly, exits must be discussed transparently. Because the worst time to discover that your incentives do not match your investors’ is when the offer is already on the table.

When I led board reporting at a gaming enterprise where I oversaw $100 million in acquisitions and post-merger integration, cap table analysis was central to every transaction. We modeled how different deal structures including cash, stock, and earnouts would flow through the cap table to various stakeholders. This visibility allowed boards to negotiate deal terms that aligned with stakeholder expectations and avoided post-closing surprises.

Why Simplicity Is a Strategic Advantage

This is also why simplicity matters. Complex structures including too many SAFEs, warrants, convertible notes, and side letters can create confusion and conflict. Complexity may serve short-term purposes but often becomes toxic during diligence. The best-run cap tables are clean, transparent, and regularly updated. They reflect not just who owns what but why.

Modern tools can help. Platforms like Carta, Pulley, and LTSE make tracking ownership more precise. But tools do not solve governance. It is the CFO’s role to ensure that the board understands dilution implications, that legal counsel is engaged early, and that the company does not create future landmines with poorly structured financings.

Ultimately, the cap table is a story. A story about how capital was raised, how people were rewarded, how decisions were made. It is a story that investors read carefully, acquirers study thoroughly, and employees absorb through the lens of their own equity grants. So tell a good story. Build a cap table that reflects thoughtfulness, not panic. One that shows how every stakeholder including founders, employees, and investors was treated fairly. One that enables, not hinders, the next round, the next hire, the next exit.

Conclusion: The Cap Table as a Mirror

Because in the end, the cap table is not just a record. It is a mirror. It shows the choices you made, the priorities you held, and the values you practiced. And if you manage it well, that mirror reflects something more than ownership. It reflects trust.

Disclaimer: This blog is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax advisor or counsel for advice tailored to your specific situation.

Hindol Datta is a seasoned finance executive with over 25 years of leadership experience across SaaS, cybersecurity, logistics, and digital marketing industries. He has served as CFO and VP of Finance in both public and private companies, leading $120M+ in fundraising and $150M+ in M&A transactions while driving predictive analytics and ERP transformations. Known for blending strategic foresight with operational discipline, he builds high-performing global finance organizations that enable scalable growth and data-driven decision-making.

AI-assisted insights, supplemented by 25 years of finance leadership experience.