The Real Power Behind Financial Leadership

It is often said that numbers speak for themselves. But in the hands of a seasoned CFO, numbers do something far more powerful: they persuade. The best CFOs do not simply report the numbers. They shape the understanding of those numbers into a narrative that informs, inspires, and when necessary, redirects the course of a company. In a world overwhelmed by data, it is not enough to be accurate. You must also be clear. And if you want to lead, you must be compelling.

Throughout my twenty-five years leading finance across cybersecurity, SaaS, manufacturing, logistics, and gaming, I have learned that the role of the CFO has quietly evolved from scorekeeper to storyteller. A CFO who cannot explain what the numbers mean is no longer viewed as credible. Worse, a CFO who explains them poorly introduces doubt, not only about the results but about the business itself. This is not marketing. It is leadership through insight.

Why Most Financial Reports Fail to Influence

Here is the uncomfortable truth: most CFOs are drowning their audiences in data while starving them of insight. Yet not all storytelling is created equal. The great CFOs do not embellish. They do not sell hype. What they do is assemble facts into frames that the audience can use to make better decisions. That is the essence of influence. It is not manipulation. It is the ability to reduce uncertainty in the room by offering a coherent view of reality that integrates the numbers with the strategy, the operations, and the human behavior that drives them both.

This is the difference between delivering a variance report and offering a narrative. The report says sales were five percent below plan. The narrative says the customer mix has shifted, pricing power is holding, but lead conversion time is stretching due to changes in procurement cycles, and here is what that means for fourth quarter planning and pipeline allocation. The former gives a fact. The latter gives direction. And in the C-suite, direction is everything.

When I rebuilt GAAP and IFRS financials for a high-growth SaaS company and designed cohort analysis frameworks, the transformation was not just technical. It was narrative. We moved from reporting monthly recurring revenue growth to explaining which customer segments were expanding, which were at risk, why expansion velocity was changing, and what actions would optimize lifetime value. The board stopped asking what happened and started asking what should we do. That shift from reactive questioning to proactive dialogue is the hallmark of effective financial narrative.

The Fatal Mistake: Precision Without Purpose

What makes this so difficult is that many CFOs were trained in disciplines that prize precision over interpretation. They came up through accounting or financial planning and analysis, where excellence meant accuracy, structure, and adherence to policy. These are non-negotiable skills. But at a certain level, they are the foundation, not the differentiator. The ability to communicate complexity simply, to connect financial data with strategic priorities, to align internal messaging with external expectations, that is the work that defines influence.

This begins with intent. A CFO must know what message they are trying to deliver before a single spreadsheet is opened. Numbers without a message are noise. Is the business under-earning relative to its potential? Is it over-investing in the wrong channels? Are we approaching an inflection point in customer behavior that requires a reallocation of resources? Are our margins masking a structural weakness in retention or pricing? These are not accounting questions. They are framing questions.

When I led board reporting at a gaming enterprise where I oversaw $100 million in acquisitions and post-merger integration, every board presentation started with a single framing question: are we creating value faster than we are consuming capital? That question organized every metric, every variance explanation, every forward projection. It gave the board a lens through which to interpret complexity and gave management a north star for decision-making.

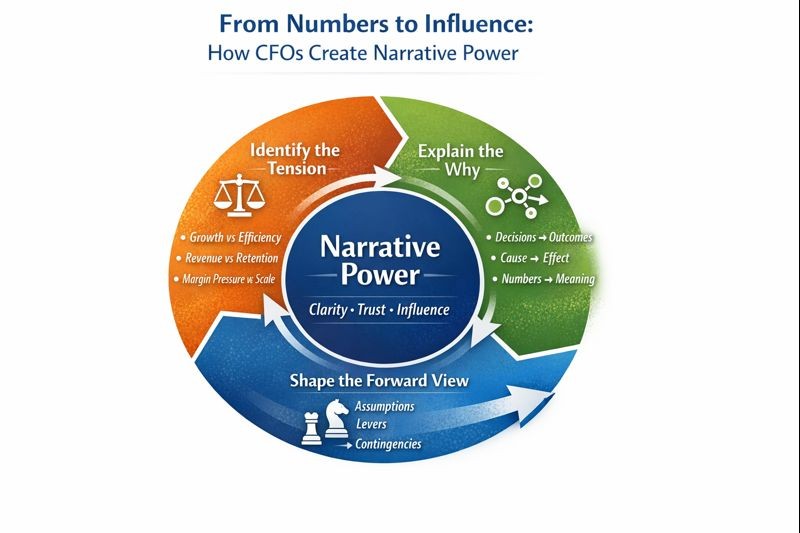

The Three Elements of Narrative Power

Element 1: Identify the Tension

Too often, CFOs rely on volume over clarity. They show up with dense board books, financial waterfalls, and pages of operational metrics. They believe that more data equals more credibility. But the opposite is often true. Boards, investors, and even executive peers are not looking for proof. They are looking for perspective.

The best financial communicators begin by identifying the tension. Every good story has one. Perhaps it is the trade-off between growth and efficiency. Perhaps it is the contradiction between top-line success and customer churn. Or maybe it is the pressure of cost inflation on gross margin even as net margin improves. Whatever it is, that tension becomes the hinge of the story. Not to dramatize but to clarify.

Element 2: Explain the Why

A CFO must be able to show the causal logic between decisions and outcomes. To explain how pricing strategy impacted churn. How hiring pace affected cost per acquisition. How procurement policy altered cash cycles. The numbers are the evidence, but the story is in the interpretation. Done right, this builds trust. Because it shows the CFO is not just watching the business. They are understanding it.

When I managed global finance for a $120 million logistics organization and overhauled freight, warehouse management, and last-mile logistics processes to reduce logistics cost per unit by 22 percent, the narrative to stakeholders was not about cost cutting. It was about creating operational leverage that would allow us to serve more customers at higher margin while maintaining service quality. Same numbers, different frame.

Element 3: Shape the Forward View

That trust becomes influence when the CFO begins to shape the forward view. A compelling narrative does not just describe the past. It guides the future. It shows where the business is going and what assumptions underpin that path. It identifies the levers that matter. It lays out contingencies. It proposes a way forward with the calm confidence of someone who sees the full chessboard.

When Bad News Requires Better Narrative

This skill is even more critical when delivering bad news. Numbers that disappoint cannot be softened, but they can be explained. The worst thing a CFO can do is deliver bad results with no narrative. It leaves the board or CEO to fill in the blanks, and they rarely do so charitably. But a CFO who shows up with a clear explanation, acknowledges what was misjudged, and presents a plan for course correction earns respect, not doubt.

When I reduced monthly burn from $800,000 to $200,000 at an email marketing SaaS company, the narrative was not we failed to grow. It was we identified that our customer acquisition model was unsustainable at scale, we preserved core capabilities while eliminating waste, and we now have 18 months of runway to prove a more capital-efficient path to profitability. Same painful reality, but framed as strategic discipline rather than operational failure. That framing determined whether investors stayed or fled.

External Markets and Internal Culture

The same applies in external communication. Investors may pretend to want perfection, but what they value more is predictability and integrity. A CFO who tells a consistent story, explains changes with transparency, and links capital deployment to long-term value creation earns premium multiples over time. When the CFO controls the narrative, they influence not just perception but price.

When I secured $40 million in Series B funding and an $8 million credit line at a nonprofit organization, the investment narrative was not about programmatic success alone. It was about a sustainable model where mission impact and financial sustainability reinforced each other. That narrative attracted mission-aligned investors who stayed through volatility because they understood the model, not just the moment.

Narrative fluency also has internal impact. Teams take cues from what leaders emphasize. If the CFO’s message is always about cost control, innovation stalls. If it is always about growth at any cost, discipline erodes. But if the CFO tells a story of balanced ambition, of growth that is efficient, risk that is measured, and decisions that are tied to long-term returns, then the finance function becomes a moral compass for the business.

When I built enterprise KPI frameworks using MicroStrategy, Domo, and Power BI tracking bookings, utilization, backlog, annual recurring revenue, pipeline health, customer margin, and retention, the narrative we built around these metrics shaped behavior. We did not just track utilization. We told a story about how optimal utilization created capacity for innovation without burnout.

The Transition Advantage

The narrative advantage is most powerful in moments of transition. A new product. A market downturn. A funding event. A change in leadership. These are moments when confidence is fragile and decisions are magnified. In these moments, the CFO becomes not just a custodian of capital but a steward of belief. Because belief, when grounded in evidence and framed with clarity, is the fuel that keeps a business moving forward.

When I improved month-end close from 17 days to under six days at a cybersecurity firm, the narrative was not about process efficiency alone. It was about creating the organizational capacity to make faster, better-informed decisions. It was about treating finance as a real-time strategic partner rather than a monthly historian. That narrative shifted how other departments viewed finance, from compliance burden to competitive advantage.

My certifications as a CPA, CMA, and CIA provide the technical foundation for financial credibility. But what creates influence is the ability to translate that technical expertise into narratives that move people. Numbers are the language of business, but narrative is the language of leadership. And leadership, at its core, is about moving people toward a shared vision of what is possible.

Conclusion

In the end, numbers do matter. They matter enormously. But in a world drowning in numbers, what matters more is the ability to make them matter to others. To connect dots. To reveal meaning. To build conviction. That is the work of the modern CFO. And it is a skill worth mastering. Because when you can move people through numbers, you are no longer just reporting the business. You are shaping it.

The finance leaders who master narrative fluency will define the next generation of value creation, not through manipulation or spin, but through the disciplined art of making complexity clear, making data meaningful, and making truth compelling. That is how the best CFOs influence through numbers.

Disclaimer: This blog is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax advisor or counsel for advice tailored to your specific situation.

Hindol Datta is a seasoned finance executive with over 25 years of leadership experience across SaaS, cybersecurity, logistics, and digital marketing industries. He has served as CFO and VP of Finance in both public and private companies, leading $120M+ in fundraising and $150M+ in M&A transactions while driving predictive analytics and ERP transformations. Known for blending strategic foresight with operational discipline, he builds high-performing global finance organizations that enable scalable growth and data-driven decision-making.

AI-assisted insights, supplemented by 25 years of finance leadership experience.