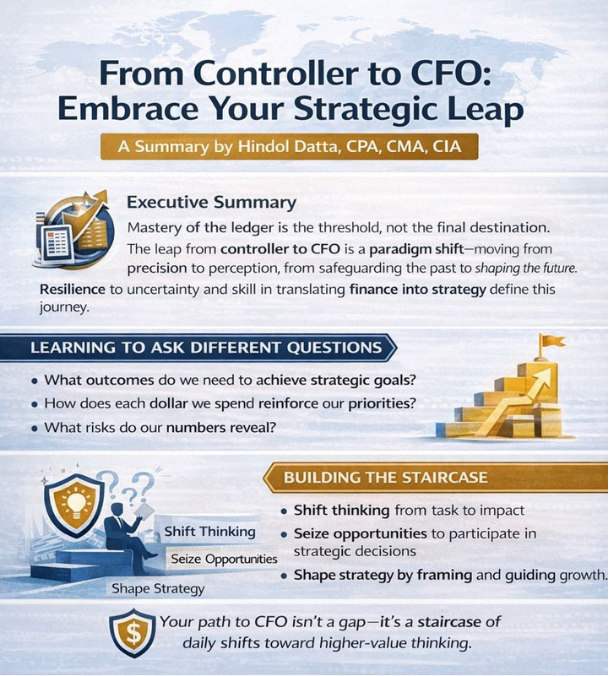

Executive Summary

There comes a point in every finance professional’s journey when mastery of the ledger, precision in close cycles, and fluency in GAAP is no longer the final destination. It is the threshold. For controllers who have spent years building the architecture of compliance and reliability, the question arises not out of dissatisfaction but from momentum. Where do I go from here? The answer, increasingly, lies not in sharpening debits and credits but in broadening vision, transforming from a steward of the past to an architect of the future. The leap from controller to CFO is not just a promotion. It is a paradigm shift. It is moving from precision to perception, from policy to possibility, from correctness to consequence. Throughout my twenty-five years leading finance across cybersecurity, SaaS, manufacturing, logistics, and gaming, I have learned that this transformation begins not with a title change but with a mindset shift. A great controller ensures the books close on time. A future CFO asks what story the numbers are telling.

The Paradigm Shift

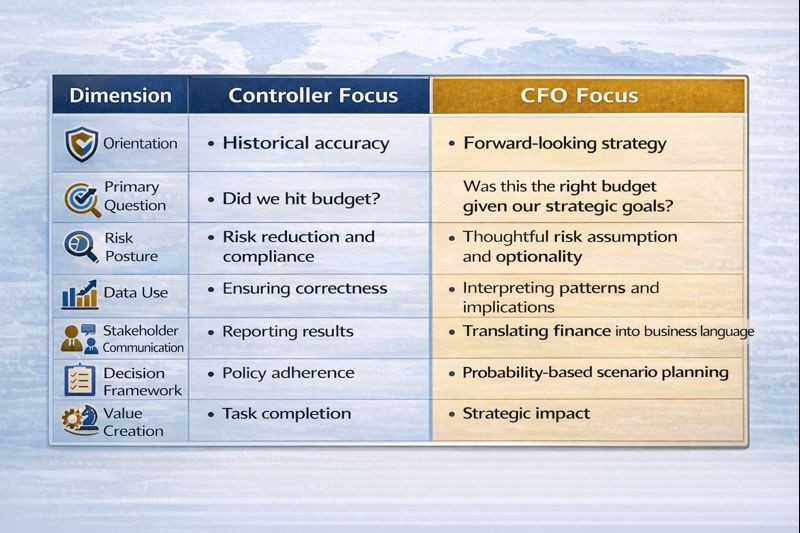

The transformation from controller to CFO requires a fundamental shift in perspective. Controlling is about safeguarding. It is rooted in the reduction of risk, in protecting the company from error, and in ensuring that what is reported is consistent, compliant, and complete. Strategy, on the other hand, is about the thoughtful assumption of risk, placing bets, designing outcomes, and imagining futures that do not yet exist.

Controller vs. CFO Mindset

When I improved month-end close from 17 days to under six days at a cybersecurity firm, the controller’s work was ensuring accuracy and completeness. The CFO’s work was asking what insights we could extract earlier to inform real-time decisions. When I implemented NetSuite and OpenAir PSA to automate revenue recognition and project accounting, the technical implementation was controller work. The strategic decision to invest in automation that would enable 28 percent accuracy improvement while freeing capacity for higher-value analysis was CFO work.

Learning to Ask Different Questions

Many controllers hesitate at this leap because they have been conditioned to believe that only the loudest person in the room is strategic. But strategy is not volume. It is clarity. It is the ability to see pattern in noise, to frame decisions under uncertainty, and to assign value to paths not yet taken. And no one is better positioned to do that than the person who understands the machine of the business, not just its mechanics but its drivers.

That insight, earned in the trenches of month-end, refined in the fires of audit, and codified in systems, gives the controller a unique advantage. They know where the friction is. They see where cash stalls. They understand the root causes of inefficiency long before the profit and loss statement reveals them. The controller’s map is detailed. What is needed next is altitude. Altitude comes from learning to ask different questions. Not what did we spend but what return did this spending create and can we improve the yield. Not are controls in place but what do these controls say about our risk appetite and adaptability as a business.

When I rebuilt GAAP and IFRS financials for a high-growth SaaS company and designed cohort analysis frameworks, the controller perspective ensured technical compliance with revenue recognition standards. The CFO perspective used those same frameworks to model customer lifetime value, identify expansion opportunities, and inform pricing strategy. The data was the same. The lens was different.

Becoming a Financial Translator

The leap to strategy also requires recalibrating relationships. The controller is often the company’s financial conscience. The CFO must also be its financial translator. This means learning to speak across functions. It means making gross margin meaningful to sales, turning customer acquisition cost into conversation with marketing, and explaining cost of capital in terms that product managers can use. Finance, at the strategic level, is not a gatekeeper. It is connective tissue. The more fluent the leader, the more influence the function.

What many aspiring CFOs miss is that the seat at the table is not granted by technical merit alone. It is earned through perspective. Boards and CEOs do not ask who knows ASC 606. They ask who can help me understand what this means for how we price, package, and scale our product in the next 18 months. The controller brings the depth. The strategist adds direction.

When I led board reporting at a gaming enterprise where I oversaw $100 million in acquisitions and post-merger integration, the work was not explaining accounting treatments. It was translating financial performance into strategic insights about which acquisitions created value, which integration approaches worked, and where future investments should focus. When I secured $40 million in Series B funding and an $8 million credit line at a nonprofit organization, the work was not producing financial statements but framing the organization’s financial story in ways that aligned with investor theses and mission impact.

Embracing Uncertainty and Impact

To make the leap, controllers must also embrace uncertainty. This is uncomfortable for those who pride themselves on accuracy and closure. Strategy rarely arrives with certainty. Instead, it comes as a probability distribution. The task is not to be exactly right but to be directionally correct and dynamically adaptive. That shift, from reconciliation to hypothesis, from audit trail to optionality tree, is the core evolution. It is not abandonment of rigor. It is the application of rigor to possibility, not just precision.

The most effective transitions happen when the controller stops defining their value by task and starts defining it by impact. Closing the books is a task. Helping a company understand how long its runway can stretch under different growth scenarios is impact. Reconciling accounts is a task. Guiding the leadership team through an equity financing decision with a clear view of dilution, ownership, and strategic leverage is impact.

When I managed global finance for a $120 million logistics organization and overhauled freight, warehouse management, and last-mile logistics processes to reduce logistics cost per unit by 22 percent, the controller work was tracking costs accurately. The CFO work was modeling how different operational configurations would impact unit economics, identifying the highest-leverage improvements, and building the business case that justified transformation investment.

Building the Staircase

It is worth noting that many CFOs today came through the controller route. Not through investment banking. Not through financial planning and analysis. But through deep operational finance. Their elevation came not from charisma but from context. They built trust. They demonstrated judgment. And when the moment came to choose someone who knew both the detail and the direction, they were the logical choice. They did not need to reinvent themselves. They needed to reveal themselves.

This revelation often requires narrative skill. Strategy lives in language. A controller who wishes to ascend must learn to frame insights, not just surface variances. They must stop handing out reports and start delivering recommendations. This does not mean becoming a storyteller for its own sake. It means owning the narrative so that data leads to decisions.

When I built enterprise KPI frameworks using MicroStrategy, Domo, and Power BI tracking bookings, utilization, backlog, annual recurring revenue, pipeline health, customer margin, and retention, the controller work was ensuring data accuracy and consistency. The CFO work was creating narrative around what the metrics meant, what actions they should trigger, and how they connected to strategic priorities. Power in finance lies not in the spreadsheet but in the sentence that explains why the numbers matter.

For some, this transition will be internal, growing within the company and slowly taking on strategic responsibilities as trust grows. For others, it may require a shift into a smaller company where the controller must wear more hats, or into a fast-growing one where finance is still being built. In either case, the path is not linear. It is iterative. The future strategist says yes more often. They volunteer for investor decks. They join pricing meetings. They sit in on go-to-market discussions.

At a digital marketing company where we scaled revenue from $9 million to $180 million, controllers who made the leap were those who engaged beyond their functional boundaries. They attended product reviews. They participated in customer negotiations. They joined board meetings not just to present financials but to contribute strategic perspective. That visibility and value creation earned them broader mandates.

Technical skill will always matter. But at the C-suite, what separates the effective from the exceptional is judgment. That judgment is not taught. It is accumulated by watching decisions unfold, by being wrong and recalibrating, by understanding incentives, constraints, and the psychology of teams under pressure. The controller who seeks to lead must move beyond clean books and into messy decisions. Because it is in those decisions that real influence is forged. My certifications as a CPA, CMA, and CIA provided technical credibility. But what created leadership opportunities was applying that technical foundation to strategic problems with business judgment.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the leap into the C-suite is not a jump over a gap. It is a staircase. One built from daily shifts in how you frame problems, ask questions, interpret data, and engage with leadership. It is about replacing the certainty of answers with the discipline of inquiry. And it is about understanding that while accounting is retrospective, leadership is prospective. There is nobility in the controller role. It is the backbone of every well-run company. But there is also calling in the strategist’s path. Not because it pays more. Not because it offers prestige. But because it allows the financial mind to shape the future, not just report the past. And that, for those with the courage to make the shift, is where the real adventure begins.

Disclaimer: This blog is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax advisor or counsel for advice tailored to your specific situation.

Hindol Datta is a seasoned finance executive with over 25 years of leadership experience across SaaS, cybersecurity, logistics, and digital marketing industries. He has served as CFO and VP of Finance in both public and private companies, leading $120M+ in fundraising and $150M+ in M&A transactions while driving predictive analytics and ERP transformations. Known for blending strategic foresight with operational discipline, he builds high-performing global finance organizations that enable scalable growth and data-driven decision-making.

AI-assisted insights, supplemented by 25 years of finance leadership experience.