Executive Summary

In nearly every boardroom I have sat in over the last decade, whether for a software as a service company scaling toward profitability or a logistics platform wrestling with seasonality and burn, some version of the same tension unfolds. We want faster decisions, sharper forecasts, leaner operations. Yet we also want rigor, transparency, and accountability. Having managed board reporting for organizations that raised over one hundred twenty million dollars in capital and executed over one hundred fifty million dollars in acquisition transactions, I have witnessed this tension firsthand. Enter the era of the synthetic analyst. These are not human employees but artificial intelligence agents, machine collaborators embedded across finance, operations, product, legal, and customer functions, delivering insights, forecasts, risk assessments, and next-best actions. As these agents take on a more visible role in corporate reasoning, boards face urgent questions. Not just can we trust the number but can we trust the reasoning that led to it. This article explores agent explainability, reproducibility, and how boards should view artificial intelligence-augmented forecasts not as truth but as testable hypotheses requiring governance frameworks that ensure transparency, accountability, and continuous validation.

The Rise of Synthetic Analysts

A traditional financial analyst compiles reports, builds models, checks assumptions, and delivers insight in a weekly or monthly cadence. A synthetic analyst, an artificial intelligence agent trained on historical data, logic flows, and business rules, can do this hourly or in real time. It does not simply recite facts. It connects signals, applies probabilistic logic, generates memos, and adjusts recommendations based on updated inputs.

In one medical technology company, the CFO deployed a synthetic analyst to monitor cash conversion cycles. The agent not only flagged anomalies in receivables turnover but also tied them to recent changes in payer mix and contract terms. It then proposed changes to working capital policy based on simulated impacts across three quarters. That analysis, which previously required two analysts and a director, now took minutes. But when presented at the board, the question shifted. Is this correct became what did the model assume. That question underscores the board’s new role, not just validating numbers but understanding how intelligence is being constructed.

Having led financial planning and analysis across organizations from startups to growth-stage companies to established enterprises, I learned that the questions boards ask reveal their governance maturity. Early-stage boards focus on results. Mature boards focus on process and assumptions. Artificial intelligence-augmented decision-making demands this higher-order scrutiny because the process is no longer entirely visible.

Explainability as Strategic Imperative

The most pressing demand from boards is not simply show your work but explain your reasoning. Synthetic analysts must provide explainable artificial intelligence outputs, not just black box results. Every forecast, recommendation, or insight should include the source data used including timeframes, systems, and data confidence levels; the assumptions applied including growth rates, model boundaries, and confidence intervals; the logic path showing what triggered the recommendation or flagged the anomaly; and the counterfactuals considered showing what the agent chose not to recommend and why.

Explainability does not just build trust. It enables challenge. In boardrooms, we do not need artificial intelligence to be right all the time. We need it to be auditable and debatable. My background as a Certified Internal Auditor emphasizes this principle. Internal controls are effective not because they prevent all errors but because they make errors detectable and correctable. Explainable artificial intelligence serves the same function. It makes reasoning visible so that flawed logic can be identified and corrected.

In an education technology company, we ran forecasting agents with the instruction to document every step. When forecasts deviated materially, the agent explained that it re-weighted trailing churn data due to new usage patterns. That explanation, paired with a comparison to the manual model, gave the board the confidence to move forward, not because the agent was perfect but because it was transparent.

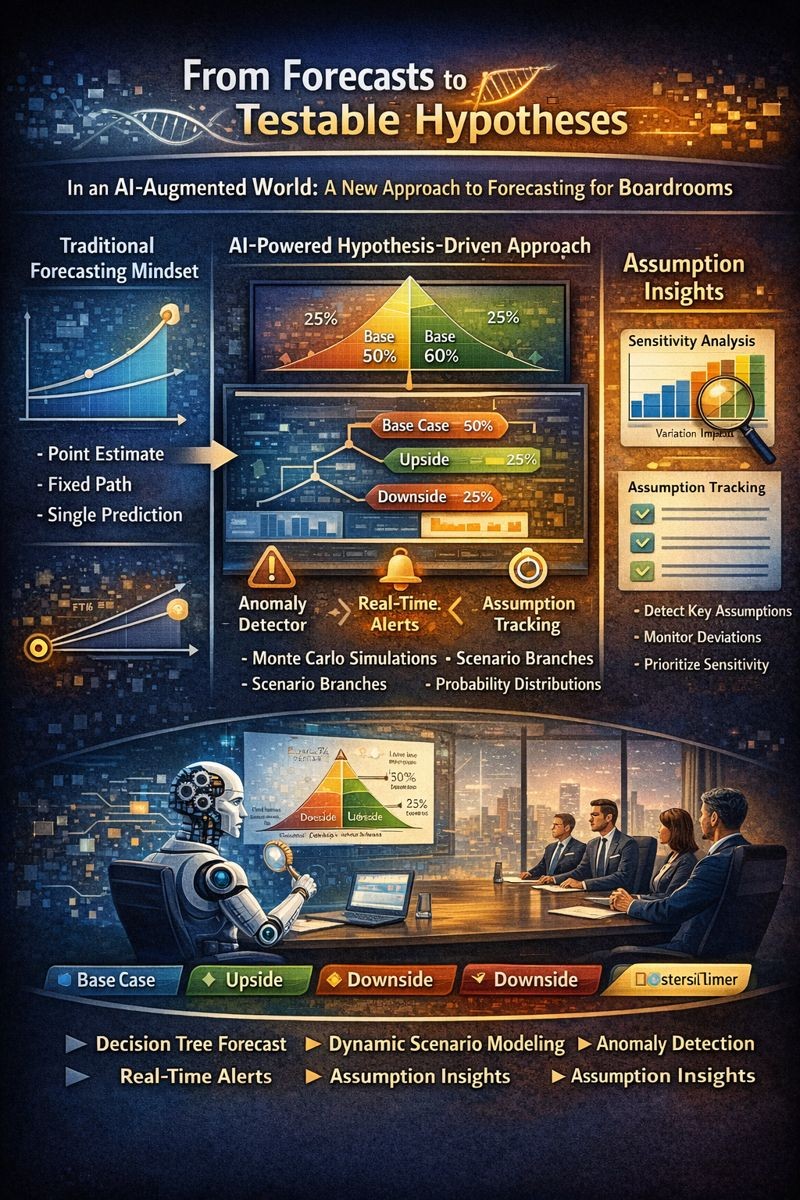

From Forecasts to Testable Hypotheses

Boards must also adjust their mindset around forecasting. In the past, a forecast was seen as a commitment or a prediction. In an artificial intelligence-augmented world, forecasts should increasingly be viewed as hypotheses, plausible outcomes conditioned on assumptions, which should be tested, tracked, and updated dynamically. This is where synthetic analysts shine. They can run multiple scenario branches simultaneously. They can detect deviations early. And they can frame forecasts as decision trees, not linear trajectories.

In practice, that means the board does not just receive a point estimate. They receive a base case, upside, and downside forecast; the probability distribution across those cases; the assumptions that drive divergence between paths; and anomaly detectors that alert when reality begins to diverge from modeled expectation. That is a fundamentally different relationship to planning. It is planning as a process, not a static artifact.

Having built financial models and created scenario analyses for organizations raising capital and executing acquisitions, I learned that the most valuable forecasts are those accompanied by sensitivity analysis showing which assumptions matter most. Artificial intelligence amplifies this by generating dozens of scenarios instantly, but the principle remains: understanding assumption sensitivity is more valuable than precision in point estimates.

Reproducibility and Audit Trails

Another key governance principle is reproducibility. If a synthetic analyst recommended a capital reallocation two months ago, can we recreate the inputs and logic that led to that suggestion? CFOs must ensure that synthetic analysts maintain versioned model states and prompt structures; input logs and pre-processed datasets; output summaries with timestamped rationales; and override records documenting when and why human intervention occurred.

This creates an audit trail not just for compliance but for institutional learning. If a model makes a poor recommendation, we must know whether the flaw was in the data, the logic, the training corpus, or the framing of the question. This is where the synthetic analyst differs from the spreadsheet. It remembers, explains, and adapts. But only if we design for traceability from the start.

My experience implementing Sarbanes-Oxley controls and managing internal audit functions across organizations including a public gaming company taught me that audit trails must be contemporaneous, complete, and tamper-evident. The same standards apply to artificial intelligence systems making material decisions. Every recommendation must be traceable from input through logic to output, with clear documentation of assumptions, thresholds, and escalations.

Human-in-the-Loop as Core Design Principle

Despite their sophistication, synthetic analysts are not decision-makers. They are decision-support agents. Boards must ask explicitly: Which recommendations require human override? What thresholds determine whether an agent’s output is final or flagged? Who owns the validation of artificial intelligence-augmented decisions in each function?

In one software as a service company, the synthetic analyst flagged a spike in customer churn and proposed reallocating sales capacity toward mid-market. The chief revenue officer disagreed, citing upcoming renewal events and qualitative insights. That disagreement was logged, the model updated, and the override captured. The process was not one of deference but dialogue. Artificial intelligence’s role is to frame the decision, not make it in isolation. Human-in-the-loop is not a limitation. It is a feature of trust.

Throughout my career building finance teams across multiple sectors and managing operations spanning from nine million to one hundred eighty million dollars in revenue, I learned that the best decisions combine quantitative analysis with qualitative judgment. Artificial intelligence excels at the former. Humans must provide the latter. Organizations that embrace this division of labor will make better decisions than those that rely on either alone.

What Boards Must Ask

As synthetic analysts proliferate, boards should embed new questions into standard oversight. Where are artificial intelligence agents actively shaping business decisions today? What explainability frameworks are in place to validate agent outputs? How are forecasts monitored and recalibrated over time? What is our override rate, and what does it say about model reliability? Do we have clear escalation paths when agent recommendations conflict with human intuition or policy?

These are not questions for the chief technology officer alone. They are questions for the entire board, especially the audit and risk committees. Because in an artificial intelligence-native operating model, risk shifts from execution failure to logic failure. Having served on boards and managed board reporting across multiple organizations and sectors, I learned that effective boards govern what they understand. If boards do not understand how artificial intelligence systems reason, they cannot govern them effectively.

Conclusion: The Strategic Advantage of Responsible Intelligence

Ultimately, the companies that thrive in this new operating landscape will not be those with the flashiest models. They will be those that build oversight into their intelligence fabric. That means designing agents for auditability, framing decisions as testable hypotheses, maintaining human accountability even when machines generate insight, and training boards to engage not just with financials but with cognitive systems.

I believe that synthetic analysts will become as common as customer relationship management systems in the next five years. But only companies that treat them with the same rigor, control, and strategic intent as any other critical system will derive lasting value. In this new era, speed is not the differentiator. Explainable speed is. And the best boards will not fear synthetic analysts. They will learn to interrogate them, just as they would any high-performing, fast-thinking analyst with a point of view.

Based on thirty years of financial leadership, board service, and strategic advisory across diverse sectors and situations, from startups to public companies, I can attest that governance frameworks determine whether new capabilities create value or chaos. Artificial intelligence is the most powerful decision-support capability we have ever developed. But power without governance is risk. The boards and CFOs who build explainability, reproducibility, and human oversight into their artificial intelligence architectures will harness this power responsibly. Those who do not will discover that unexplainable speed compounds errors as quickly as it generates insights.

Disclaimer: This blog is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax advisor or counsel for advice tailored to your specific situation.

Hindol Datta is a seasoned finance executive with over 25 years of leadership experience across SaaS, cybersecurity, logistics, and digital marketing industries. He has served as CFO and VP of Finance in both public and private companies, leading $120M+ in fundraising and $150M+ in M&A transactions while driving predictive analytics and ERP transformations. Known for blending strategic foresight with operational discipline, he builds high-performing global finance organizations that enable scalable growth and data-driven decision-making.

AI-assisted insights, supplemented by 25 years of finance leadership experience.