Executive Summary

In boardrooms across industries, a familiar question now emerges with increasing urgency: Are we using artificial intelligence? It is often followed by a more uncertain one: Should we worry about it? As someone who has served CFO roles across verticals, from software as a service and medical devices to freight logistics and nonprofit sectors, managing board reporting for organizations that raised over one hundred twenty million dollars in capital and executed over one hundred fifty million dollars in acquisition transactions, I have seen how board priorities evolve. What was once curiosity about digital transformation has become a matter of fiduciary oversight. Simultaneously, capital allocation has been fundamentally altered. Where a company chooses to invest, whether in headcount, systems, marketing, or innovation, reflects its strategic intent more clearly than any investor memo or product roadmap. The emergence of intelligent agents powered by generative artificial intelligence and embedded deeply within finance, operations, and customer engagement has fundamentally altered this equation. Artificial intelligence does not merely support functions. It increasingly replaces marginal decisions, supplements judgment, and augments productivity at a scale traditional headcount cannot match. This article explores how boards must govern artificial intelligence as a fiduciary imperative and how CFOs must rethink capital allocation in the age of intelligent systems.

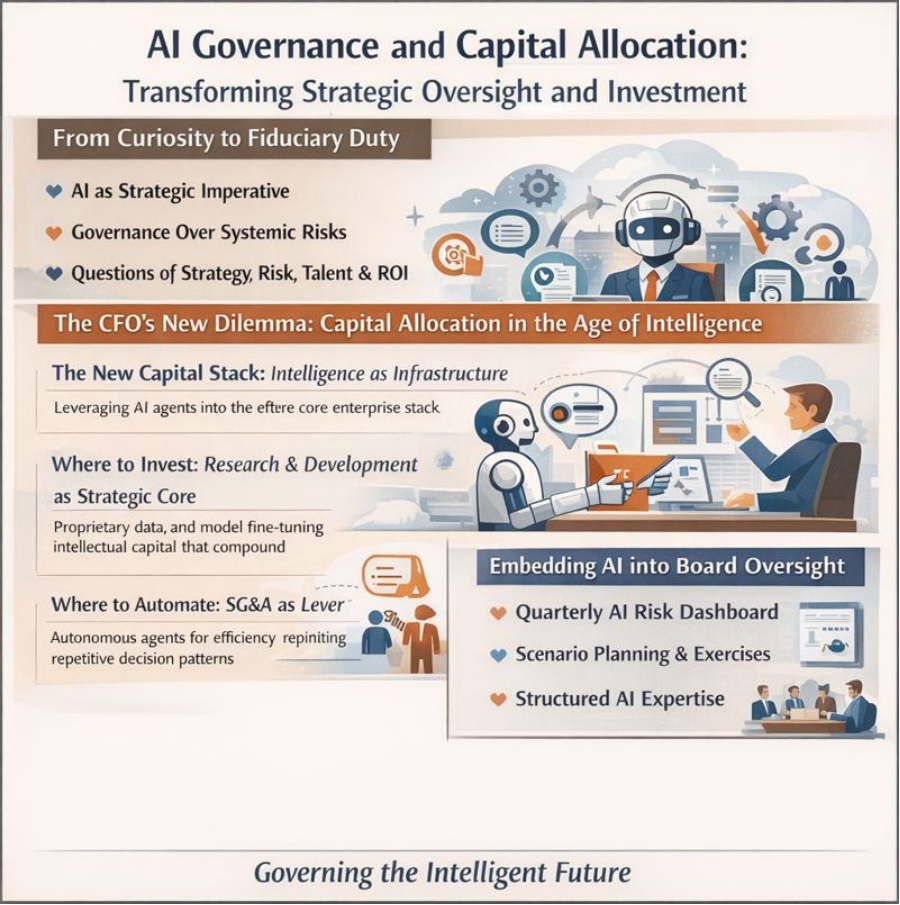

From Curiosity to Fiduciary Duty

Artificial intelligence is no longer a research and development topic or a back-office efficiency play. It sits squarely within enterprise risk, strategic advantage, and regulatory exposure. For boards of companies from Series A through publicly traded enterprises, the question is no longer whether to engage but how to govern effectively. Artificial intelligence is not simply a tool. It is a decision system. And like any system that influences financial outcomes, customer trust, and legal exposure, it demands structured oversight.

Having implemented Sarbanes-Oxley controls and managed internal audit functions across organizations including a public gaming company, I learned that governance frameworks must evolve with business complexity. Artificial intelligence introduces new complexity requiring new oversight mechanisms. Boards must now treat artificial intelligence with the same discipline they apply to capital allocation, mergers and acquisitions due diligence, and cybersecurity. This is not a technical responsibility. It is a governance imperative.

The emergence of intelligent agents that perform financial forecasting, customer interaction, legal document review, and risk scoring creates a new kind of operational leverage but also introduces a new layer of systemic risk. Artificial intelligence models are dynamic. They are probabilistic. They learn and adapt. They may hallucinate. They may encode bias. And unlike human operators, they do not always explain their reasoning.

In one company I advised, an artificial intelligence-driven pricing assistant proposed a multi-tiered pricing change that, while mathematically sound, introduced legal risk due to regional price discrimination laws. No one had thought to vet the model through a legal lens. The output was live before risk was even considered. The lesson was clear: artificial intelligence can act faster than governance unless governance is actively embedded.

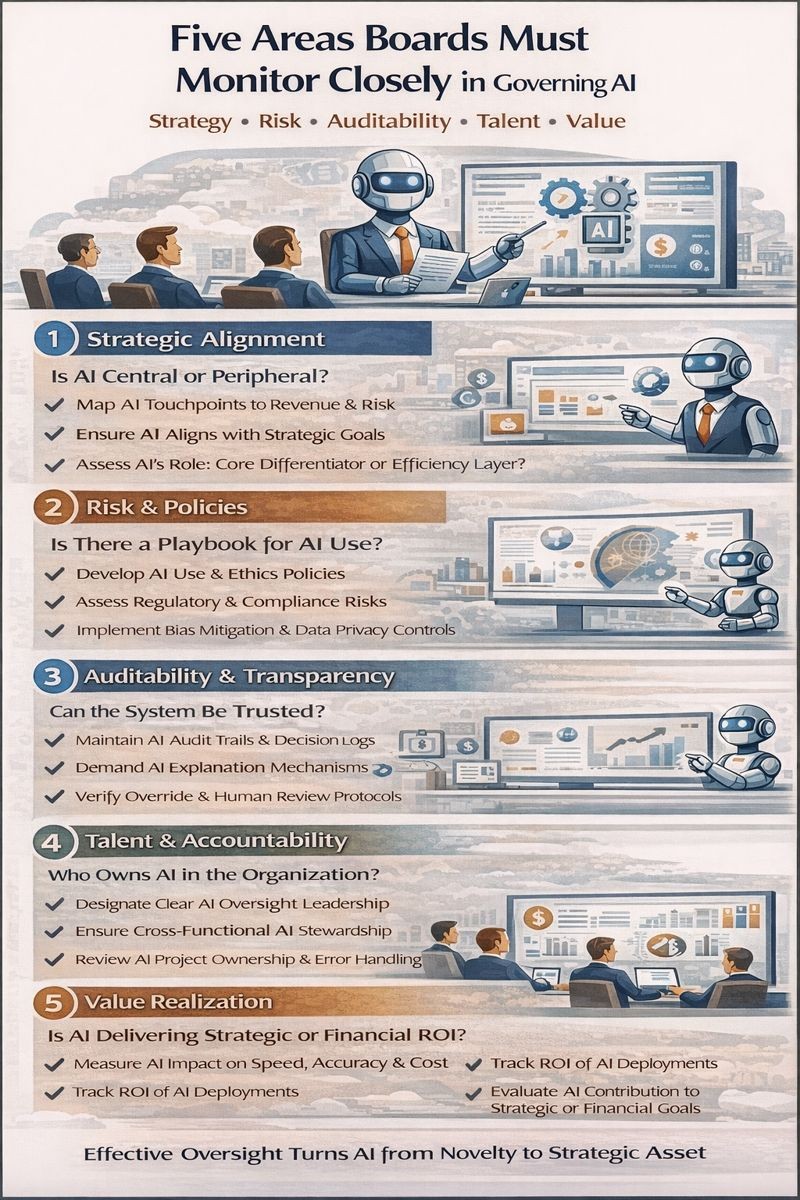

Five Areas Boards Must Monitor Closely

To govern artificial intelligence effectively, boards must anchor their oversight in five key areas: strategy, risk, auditability, talent, and value realization. Each deserves explicit attention, recurring visibility, and structured inquiry. My background as a Certified Internal Auditor informs this governance framework. Just as we audit financial processes for control effectiveness, we must audit artificial intelligence systems for strategic alignment, risk management, and accountability.

Strategic Alignment: Is AI Central or Peripheral?

Boards must ask: what role does artificial intelligence play in the company’s core value proposition? Is it foundational to the product or merely an efficiency layer? If it is central, governance must go deeper. If it is peripheral, boards must ensure it does not introduce disproportionate risk. For example, a generative artificial intelligence engine powering a legal search platform carries very different exposure than an artificial intelligence-enabled expense categorization tool. One may affect contract interpretation. The other optimizes travel and entertainment coding. Both use artificial intelligence. But only one touches critical judgment.

Boards should request an AI Materiality Matrix, a map that shows where artificial intelligence touches customers, decisions, revenue, and risk. That map should evolve as the product evolves. Having designed enterprise key performance indicator frameworks using business intelligence tools including MicroStrategy and Domo, I learned that visibility enables oversight. Without clear mapping of where artificial intelligence operates and what it influences, boards cannot fulfill their fiduciary responsibility.

Risk and Policy Frameworks: Is There a Playbook for AI Use?

Too many companies deploy artificial intelligence without explicit policy. Boards must demand one. This policy should cover model selection criteria, acceptable use, prohibited use, bias mitigation strategies, privacy protections, third-party dependency risks, and fallback protocols. For instance, if a customer service agent is powered by generative artificial intelligence, what happens when the model misclassifies a complaint? Who owns the correction? Is it auditable? Is it remediable?

Boards should also ask if the company has mapped its artificial intelligence exposure to regulatory regimes: General Data Protection Regulation, California Consumer Privacy Act, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and emerging global artificial intelligence laws like the European Union AI Act. Compliance may not be required yet, but readiness signals maturity.

Auditability and Explainability: Can the System Be Trusted?

Any artificial intelligence system that affects customers, employees, or financial outcomes must be auditable. That means the company must maintain model logs, decision traces, override capabilities, and a method to explain why a decision was made. In one advertising technology company where I led financial planning and analysis, we discovered that a generative artificial intelligence recommendation engine was optimizing for click-throughs at the expense of user experience. No one knew how the model had made that tradeoff. There was no audit trail. We had to retrain the system and rebuild trust.

Boards must ask: What mechanisms exist for artificial intelligence explainability? Are humans able to override artificial intelligence decisions? Can the company reproduce results under scrutiny? In regulated industries, this becomes not just good governance but survival. My experience implementing internal controls and audit frameworks taught me that auditability is non-negotiable for critical systems. Artificial intelligence systems making material decisions must meet the same standard.

Talent and Accountability: Who Owns AI in the Organization?

Artificial intelligence systems need stewardship. Boards must ensure there is a clearly identified artificial intelligence governance leader, ideally reporting to the chief executive officer, CFO, or chief risk officer, who owns oversight of artificial intelligence projects. In smaller firms, this may be a cross-functional artificial intelligence committee that includes finance, legal, engineering, and product. The board must ensure that someone is accountable not just for deploying artificial intelligence but for monitoring its behavior, documenting its evolution, and correcting its errors.

The question to ask is: who is on point if the model goes wrong? Without that clarity, artificial intelligence risk becomes an orphaned liability. Throughout my career building and managing finance teams across multiple organizations and sectors, I learned that accountability determines execution quality. Clear ownership drives performance. Ambiguous responsibility creates gaps.

Value Realization: Is AI Delivering Strategic or Financial ROI?

Boards must differentiate between artificial intelligence as novelty and artificial intelligence as leverage. Ask not just what is being automated but what is being improved. Are decisions faster? Is forecast accuracy better? Is risk reduced? Is margin enhanced? In one nonprofit where I served as CFO, an artificial intelligence system was deployed to improve grant application triage. It succeeded, cutting review time by forty percent. But we failed to measure the quality of outcomes. Grant rejection accuracy dropped. False positives increased. The system optimized for speed, not fairness. We had to roll back.

Boards should expect artificial intelligence return on investment to be tracked with rigor: quantified impact, timelines, and cost-benefit ratios. Vanity metrics will not suffice. Strategic alignment and clear key performance indicators must drive artificial intelligence investments. My experience managing capital allocation and tracking return on investment across organizations that scaled from nine million to one hundred eighty million dollars in revenue taught me that what you measure shapes behavior. If we measure artificial intelligence deployment, we get adoption. If we measure artificial intelligence impact, we get value.

The CFO’s New Dilemma: Capital Allocation in the Age of Intelligence

The emergence of intelligent agents has fundamentally altered capital allocation. Artificial intelligence does not merely support functions. It increasingly replaces marginal decisions, supplements judgment, and augments productivity at a scale traditional headcount cannot match. We must now rethink how we allocate capital, not just for growth but for leverage. Capital allocation has always been a test of discipline. In my three decades of experience across sectors and stages, from Series A software as a service to global logistics and medical devices, I have viewed capital budgeting not as a mechanical process but as a mirror. It reveals where belief meets constraint.

The New Capital Stack: Intelligence as Infrastructure

Traditionally, CFOs allocated capital into three broad domains: people, process, and product. The assumption was linearity. More people equaled more output. More spend on systems yielded better process. More product investment delivered innovation. But the rise of artificial intelligence agents breaks this logic. Now, companies can invest in systems that scale thought rather than just headcount.

In one software as a service firm, we faced a classic dilemma: increase sales operations headcount to support revenue forecasting or explore an artificial intelligence-driven planning assistant. We chose the latter. With less than half the budget originally earmarked for hiring, we deployed a generative agent trained on customer relationship management, enterprise resource planning, and product telemetry. Within six weeks, it generated forecast scenarios, flagged inconsistencies in pipeline stages, and cut the planning cycle by seventy percent. Not only did it perform the task, it improved the task. The dollars went further because the capital was deployed into intelligence, not just execution.

Where to Invest: Research and Development as Strategic Core

Research and development remains the highest-leverage function in artificial intelligence-native organizations. But it must evolve from traditional software development toward model architecture, prompt engineering, and data strategy. Generative models, when applied properly, become engines of product differentiation. But they are only as strong as the context they learn from.

Founders and CFOs must begin viewing their proprietary data pipelines as capital projects. Training a model on exclusive product usage data, support logs, or user behavior is akin to investing in a custom algorithm. That training cost, fine-tuning process, and continuous learning loop create intellectual capital that compounds over time. It is not unlike amortizing the cost of developing a patent, only here, the patent improves with use.

In one education technology company, we allocated capital to build a fine-tuned learning agent that adapted to student behavior and adjusted content sequencing dynamically. This required tagging historical performance data, anonymizing interaction logs, and deploying a custom model. It took nine months and one point two million dollars, but it doubled engagement and improved completion rates by thirty percent. That investment paid off across cohorts, not quarters. That is the new face of research and development return on investment.

Where to Automate: Selling, General, and Administrative Expenses as Lever

Selling, general, and administrative expenses have historically been cost centers. Artificial intelligence agents now challenge that perception. In customer support, compliance, finance, human resources, and procurement, autonomous agents are already outperforming traditional shared services on response time, consistency, and coverage.

In one logistics firm where I managed supply chain analytics for a one hundred twenty million dollar enterprise, reducing logistics cost per unit by twenty-two percent, we deployed a contract intelligence agent that reviewed vendor agreements, flagged inconsistencies, and recommended clause adjustments based on precedent. What previously required three legal analysts and weeks of effort became a twenty-four-hour review loop with human validation. This was not just automation. It was risk reduction with velocity. The agent became part of the team. And the team got smaller, sharper, and more strategic.

CFOs must now ask: Which selling, general, and administrative functions are driven by repetitive decision patterns? Those are prime candidates for artificial intelligence augmentation. Accounts payable workflows, travel and entertainment categorization, compliance checks, and even preliminary financial close activities are increasingly being handled by learning agents. The result is not just cost savings. It is time reallocation. The humans freed up can now focus on exception handling, scenario modeling, or cross-functional partnership.

Customer Experience: Where Automation Must Earn Its Keep

Artificial intelligence agents also promise to reshape customer experience, but this is where capital allocation must be guided by caution, not enthusiasm. Automation in customer-facing domains is powerful but brittle. When deployed poorly, it erodes trust. When designed with care, it can elevate support, personalize journeys, and generate loyalty.

In a consumer software as a service company, a generative artificial intelligence agent was deployed in customer support to resolve tier-one queries. Resolution rates improved by twenty-five percent, but satisfaction scores dropped. Why? Because the system lacked empathy design. It resolved issues but failed to understand tone, urgency, or emotional nuance. We iterated by adding sentiment analysis, escalation logic, and conversational context retention. Only then did the customer experience align with the brand promise.

CFOs must budget for not just artificial intelligence deployment but for artificial intelligence refinement. The first eighty percent of automation is often easy. The final twenty percent, the part customers remember, is where the investment must deepen. Think of customer experience agents not as automation but as productized empathy. That requires design, governance, and iteration. All of which must be budgeted.

The AI Budget Framework: Cognitive Capital

In traditional budgeting, we think in terms of fixed versus variable cost. Artificial intelligence demands a new category: cognitive capital. This includes spending on model training, reinforcement learning, data labeling, and prompt refinement. These are not just information technology costs. They are investments in capability. And like research and development, they should be tracked for return on investment across cycles.

A CFO in an artificial intelligence-era company should be able to articulate three things clearly: Which decisions are human-led, machine-supported? Which decisions are machine-led, human-supervised? Which decisions will shift categories over time, and how is capital following that migration? This is not spreadsheet modeling. It is decision architecture. My certifications spanning accounting, management accounting, internal audit, production and inventory management, and project management provide the multidisciplinary framework for designing these new capital allocation models.

Embedding AI Governance into the Board Agenda

Just as cybersecurity now appears as a recurring board topic, so too must artificial intelligence governance. Every audit committee, every risk committee, and every technology subcommittee must start including artificial intelligence oversight in their charters. This does not mean every board member must become a machine learning expert. But they must become literate in how artificial intelligence systems work, what failure modes exist, and how trust is preserved.

A quarterly AI Risk Dashboard is a good place to start, summarizing model usage, error rates, override incidents, regulatory alerts, and investment return on investment. Paired with scenario walkthroughs and tabletop exercises, this becomes not just oversight but preparedness. Having managed board reporting across multiple organizations and stages, I learned that boards govern what they see consistently. Visibility drives accountability.

Conclusion: The New Era of Strategic Leadership

The best boards I work with now treat artificial intelligence governance as a competitive advantage. They ask sharp questions, demand evidence, and support leadership with clarity. They understand that governing artificial intelligence is not about controlling algorithms. It is about stewarding judgment in a world where intelligence scales beyond human bandwidth.

Similarly, the most effective CFOs understand that capital allocation in the artificial intelligence era requires deciding where humans create differentiated value and where machines can take over. This is not about replacing people. It is about raising the floor of execution and raising the ceiling of judgment. Capital must now follow this curve. Invest where human creativity thrives. Automate where human repetition drags.

Based on thirty years of financial leadership across diverse sectors and situations, from startups to public companies, from high growth to operational optimization, I can attest that artificial intelligence represents both opportunity and obligation. The companies that win will not be those that spend the most on artificial intelligence. They will be those that govern best and allocate smartest. The boards that fulfill their fiduciary duty will be those that engage artificial intelligence as a strategic imperative, not a technical curiosity. And the CFOs who lead will be those who see artificial intelligence not as cost or capability alone, but as both, requiring governance frameworks and capital discipline that match the transformative power of intelligent systems.

The future of governance is algorithmic. The future of capital allocation is cognitive. And both futures are here.

Disclaimer: This blog is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax advisor or counsel for advice tailored to your specific situation.

Hindol Datta is a seasoned finance executive with over 25 years of leadership experience across SaaS, cybersecurity, logistics, and digital marketing industries. He has served as CFO and VP of Finance in both public and private companies, leading $120M+ in fundraising and $150M+ in M&A transactions while driving predictive analytics and ERP transformations. Known for blending strategic foresight with operational discipline, he builds high-performing global finance organizations that enable scalable growth and data-driven decision-making.

AI-assisted insights, supplemented by 25 years of finance leadership experience.