Executive Summary

There is a peculiar moment in finance, quiet and almost imperceptible, when a model’s suggestion begins to feel like a decision. It arrives not with fanfare but with familiarity. A recommendation to adjust forecast weights, a revision to a credit risk tier, a realignment of pricing parameters. It all seems helpful, rational, and unemotional. Yet as the suggestions accumulate and human hands recede, a more delicate question emerges: who is in charge here? In the age of financial artificial intelligence, this is not a hypothetical concern. It is a daily negotiation between human judgment and machine-generated logic. Having implemented financial planning and analysis automation, business intelligence systems, and operational analytics platforms across organizations spanning cybersecurity, software as a service, logistics, and professional services, I have witnessed how algorithms increasingly assist in treasury management, fraud detection, scenario modeling, procurement, pricing, and even board-level financial storytelling. The spreadsheet has evolved into a system that not only calculates but infers, predicts, and optimizes. With that evolution comes a new obligation: not to resist the machine but to restrain it, to instruct it, to guard against the drift from assistance to authority. This article explores the ethical guardrails that CFOs must establish to ensure artificial intelligence systems in finance serve their intended role as augmentation, not automation of thought.

The Shift from Assistance to Authority

Finance thrives on discipline. It is the keeper of thresholds, the defender of policy, the quiet enforcer of institutional memory. But AI systems do not remember in the way humans do. They learn from patterns, not principles. They adapt quickly, sometimes too quickly. They reward efficiency and correlation. They do not pause to ask why a variance matters or whether a cost is truly sunk. They do not understand the fragility of context.

Throughout my career implementing enterprise resource planning systems, designing key performance indicator frameworks, and building financial models across diverse industries, I have learned that context is everything. A variance that looks concerning in one environment is perfectly normal in another. A cost structure that seems inefficient in one business model is optimal in another. A pricing decision that appears suboptimal in isolation makes strategic sense when considering customer lifetime value and competitive positioning. These contextual judgments require human understanding that no algorithm can fully replicate.

Left unchecked, AI systems risk encoding biases that have never been audited, compounding errors that go unnoticed until they become embedded in the system’s logic. What begins as a helpful model can, over time, shape decisions that no longer pass through human scrutiny. This is not a crisis. But it is a caution. And the answer is not to unplug the tools but to surround them with guardrails: practical, ethical, operational structures that ensure AI systems serve their intended role.

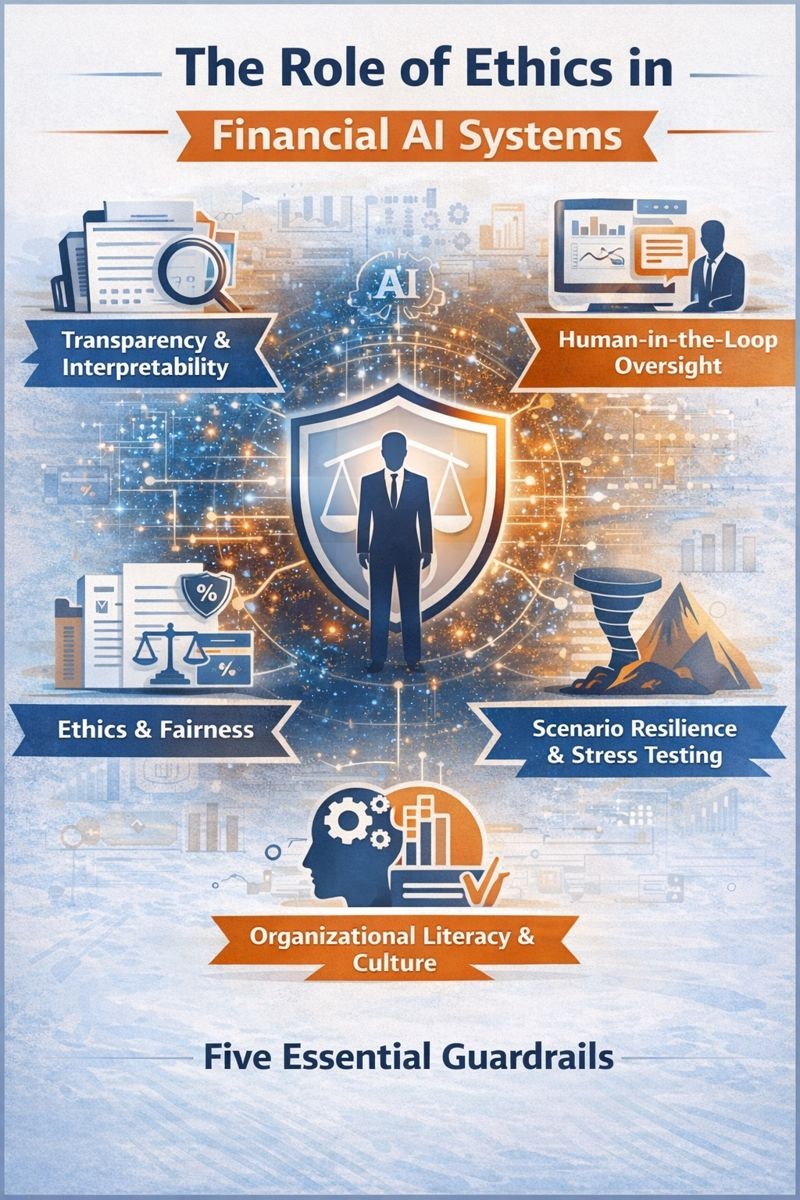

Five Essential Guardrails

First Guardrail: Transparency and Interpretability

The first guardrail is transparency, not merely of the output but of the underlying logic. Black-box models, those that produce results without exposing their reasoning, have no place in core finance. If a system cannot explain why it flagged a transaction, revised a projection, or rejected a claim, then it cannot be trusted to inform decisions. Interpretability is not a luxury. It is a governance requirement.

CFOs must demand model lineage, input traceability, and algorithmic audit trails. We must know how the machine learns, what it values, and how it handles ambiguity. My background as a Certified Internal Auditor informs this perspective. Just as we audit human-driven processes to understand decision logic and ensure appropriate controls, we must audit algorithms to understand their decision frameworks and validate their appropriateness.

When I led the implementation of business intelligence systems including MicroStrategy and Domo for tracking operational and financial metrics, one of the critical success factors was transparency in how metrics were calculated. If users did not understand how a number was derived, they would not trust it. The same principle applies to artificial intelligence systems. Finance teams must be able to trace from model output back through the logic to the underlying data, understanding each step of the reasoning process.

Second Guardrail: Human-in-the-Loop Oversight

AI should never operate autonomously in high-impact financial decisions. Forecast adjustments, pricing recommendations, capital allocations: these require human validation, not just as a matter of control but of accountability. A machine can surface an anomaly. Only a person can determine whether it matters. The best systems are designed to assist, not to replace. They invite interrogation. They offer explanations, not conclusions. In a world of intelligent systems, human intelligence remains the ultimate fail-safe.

Having led financial planning and analysis functions, managed treasury operations, and overseen capital allocation decisions across organizations from startups to growth-stage companies to established enterprises, I know that the most critical financial decisions involve judgment that cannot be algorithmic. Should we extend payment terms to a strategically important customer experiencing temporary difficulty? Should we accelerate hiring despite near-term margin pressure? Should we invest in a capability that will not generate return for eighteen months? These questions have quantitative dimensions that AI can illuminate, but they require qualitative judgment that only humans can provide.

During my time managing board reporting for organizations that raised over one hundred twenty million dollars in capital, I learned that boards want to understand not just what the numbers are but why they matter and what we intend to do about them. An AI system can produce forecasts and scenarios, but only a CFO can explain the strategic context, assess the competitive implications, and recommend actions aligned with the company’s mission and values.

Third Guardrail: Ethics and Fairness

Ethics and fairness are particularly critical in areas like credit scoring, expense flagging, and vendor selection. AI models trained on biased data can unintentionally replicate discriminatory patterns. A seemingly neutral system might deprioritize small vendors, misinterpret regional cost norms, or penalize outlier behavior that is actually legitimate. Finance cannot afford to delegate ethical reasoning to algorithms. We must build into our systems the ability to test for disparate impact, to run fairness audits, to ask not just does it work but for whom does it work and at what cost.

My experience implementing procurement systems and managing vendor relationships across global operations taught me that vendor selection involves more than just price and quality metrics. It involves relationships, risk management, strategic alignment, and often considerations of supplier diversity and economic development. An algorithm optimizing purely for cost and delivery time might systematically disadvantage small businesses or minority-owned enterprises that provide strategic value beyond the immediate transaction.

Similarly, when implementing automated fraud detection and expense monitoring systems, I learned that legitimate behavior can appear anomalous. An employee traveling internationally has different expense patterns than one working domestically. A salesperson closing a major deal may have entertainment expenses that look excessive in isolation but are appropriate in context. AI systems must be designed and monitored to avoid false positives that unfairly flag legitimate activity or create inequitable treatment.

Fourth Guardrail: Scenario Resilience and Stress Testing

AI tools are only as good as the environment they were trained in. A system trained on pre-2020 data would struggle to predict the pandemic’s liquidity shocks or supply chain collapse. Models must be stress-tested across extreme scenarios: black swans, grey rhinos, structural shifts. Finance leaders must insist on robustness checks that go beyond validation accuracy. We must model the edge cases, the tail risks, the regime changes that reveal a model’s blind spots.

Having managed financial planning through multiple economic cycles and business disruptions, from the 2008 financial crisis through the pandemic, I learned that models trained on normal conditions fail precisely when you need them most. During my time leading finance for a logistics and wholesale enterprise with one hundred twenty million dollars in revenue, we experienced supply chain disruptions, sudden currency fluctuations, and rapid shifts in customer demand patterns. The forecasting models that worked well in stable periods became unreliable during volatility.

This is why scenario planning remains essential even with sophisticated AI tools. We must stress-test models against extreme scenarios they have never seen. What happens if our largest customer disappears overnight? What if our supply chain cost doubles? What if regulatory changes fundamentally alter our business model? AI can help us model these scenarios more rapidly and comprehensively than traditional methods, but humans must define the scenarios and interpret the implications.

Fifth Guardrail: Organizational Literacy and Culture

Finally, guardrails are not just technical constructs. They are cultural. Finance teams must be trained not only to use AI tools but to question them. To understand how they work, where they fail, and when to override. The CFO’s role is not to become a data scientist, but to demand fluency in how machine intelligence intersects with financial decision-making. We must invest in talent that bridges analytics and judgment, in processes that elevate curiosity over compliance.

Throughout my career building and developing finance teams across multiple organizations, I have learned that cultural transformation is harder than technical implementation. When we automated revenue recognition at a cybersecurity company, increasing accuracy by twenty-eight percent, the technology implementation took three months. Building the organizational capability to use the system effectively, trust its outputs, and know when to investigate anomalies took over a year.

My certifications spanning accounting, management accounting, internal audit, production and inventory management, and project management reflect the multidisciplinary perspective required in modern finance leadership. Today’s CFOs must add artificial intelligence literacy to that toolkit, not at the level of engineering the algorithms but at the level of understanding their capabilities, limitations, and appropriate applications.

Empowerment, Not Replacement

It is tempting to embrace AI as a means of speed and scale, and in many respects that promise is real. AI can detect anomalies at a scale no auditor could match. It can simulate thousands of scenarios in seconds. It can reduce manual errors, accelerate closes, optimize procurement, and forecast with remarkable accuracy. But the goal is not to outrun the human. It is to empower them. The machine is not the oracle. It is the mirror, the map, the assistant. It sharpens judgment but does not replace it.

Having improved month-end close processes from seventeen days to under six days through process redesign and system automation, I understand the value of technology in eliminating routine manual work. But I also understand that the time saved from manual tasks must be reinvested in higher-value activities: strategic analysis, scenario planning, business partnership, and judgment. AI is a tool for reallocation of effort, not reduction of people.

Finance has always been a function of rigor. Of double-checking the math, of reading between the numbers, of understanding not just the statement but the story. As AI assumes a more central role in this domain, the imperative is not to cede control but to strengthen it through questions, through transparency, through design.

Conclusion

In the end, the success of AI in finance will not be measured by its autonomy but by its alignment: with strategy, with integrity, with human reason. The machine may compute, but we decide. And in that simple assertion lies both the promise and the responsibility of this new financial age.

CFOs must lead the establishment of ethical frameworks for financial AI systems. This means demanding transparency in algorithmic decision-making, maintaining human oversight of critical decisions, ensuring fairness and testing for bias, stress-testing models against extreme scenarios, and building organizational literacy that enables teams to use AI tools effectively while maintaining appropriate skepticism.

The organizations that get this right will benefit from AI’s power while avoiding its pitfalls. They will make faster, more informed decisions while maintaining the ethical standards and human judgment that finance requires. They will use AI to augment human capability rather than substitute for it. And they will build finance functions that are more intelligent, more responsive, and more trustworthy than ever before.

The tools are powerful. The risks are real. The responsibility is ours. As CFOs, we must ensure that as artificial intelligence transforms finance, it does so in ways that strengthen rather than weaken our commitment to accuracy, integrity, and sound judgment. The future of finance is not human or machine. It is human and machine, working together with clear boundaries, shared purpose, and unwavering ethical standards.

Disclaimer: This blog is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax advisor or counsel for advice tailored to your specific situation.

Hindol Datta is a seasoned finance executive with over 25 years of leadership experience across SaaS, cybersecurity, logistics, and digital marketing industries. He has served as CFO and VP of Finance in both public and private companies, leading $120M+ in fundraising and $150M+ in M&A transactions while driving predictive analytics and ERP transformations. Known for blending strategic foresight with operational discipline, he builds high-performing global finance organizations that enable scalable growth and data-driven decision-making.

AI-assisted insights, supplemented by 25 years of finance leadership experience.