Executive Summary

Most mergers fail not in the boardroom but in the back office. Not in the price paid but in the processes that follow. The real battleground is where technology meets process, where two companies with different enterprise resource planning platforms, different customer relationship management philosophies, and different assumptions about how work gets done must come together in rhythm. Having overseen more than one hundred fifty million dollars in acquisition transactions across sectors from gaming to digital marketing to logistics, I have learned that post-merger systems integration is not a tactical necessity. It is a strategic weapon. When approached with intent and precision, integration becomes the moment where legacy habits can be challenged, broken processes can be retired, and a new operating model can be built from first principles. This article explores why systems integration determines whether a deal amplifies value or quietly leaks it, and what CFOs must do to transform integration from a technical project into a strategic inflection point that reshapes how the combined enterprise operates, competes, and creates value.

Most acquisition decks look immaculate. The synergies are crisp, the models sing with logic, and the top-line narrative clicks. It all feels inevitable. But the truth is less glamorous and far more enduring. You do not win a deal when you close it. You win a deal when two companies, with different organizational DNA, different payroll systems, different sales processes, and different ideas about what a customer means, come together in rhythm. That is where strategy either amplifies or dies.

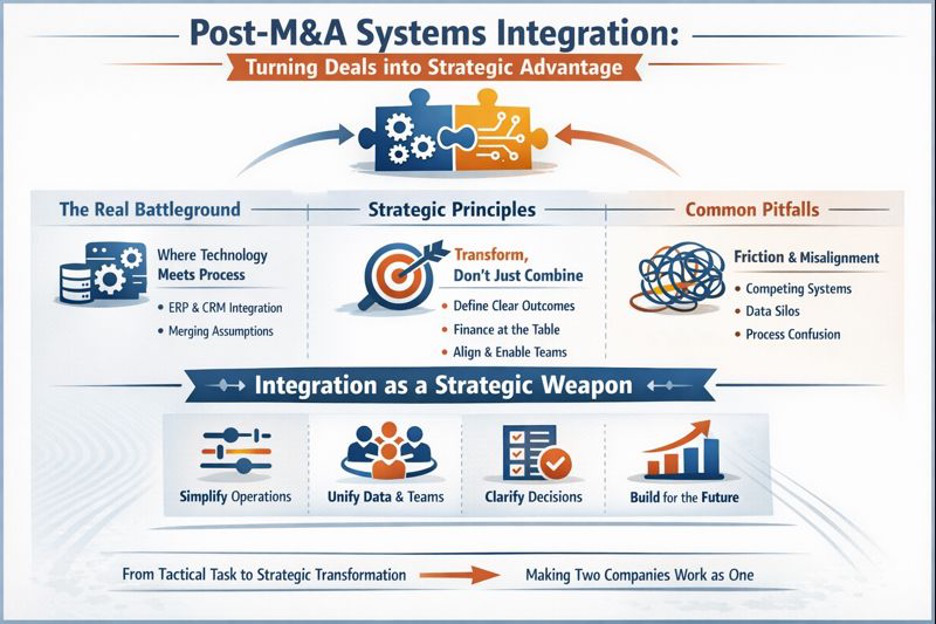

When we speak of post-merger integration, too often we think about headcount, reporting lines, brand unification, and product overlap. All of that matters. But the real battleground is where technology meets process. The temptation is to treat systems integration as a checklist: merge enterprise resource planning platforms, consolidate human resources information systems tools, streamline customer relationship management processes, rationalize data warehouses, archive legacy records. From a technical standpoint, these are sensible steps. From a strategic standpoint, they are insufficient. What you are really doing is not merging systems. You are merging assumptions about how work gets done.

Systems as Philosophy

Most systems reflect a philosophy. A Salesforce instance is not just a database. It is a theory of how deals progress and who gets credit for what. An enterprise resource planning system is not just a ledger. It is a design for how value flows through the enterprise. When you merge two of them, you are not unifying code. You are reconciling two ideologies. If you approach that reckoning passively, you will spend years debugging organizational confusion.

Throughout my career implementing enterprise resource planning systems including NetSuite and Oracle Financials, integrating professional services automation platforms like OpenAir, and connecting financial systems to Salesforce across multiple organizations, I have seen this play out repeatedly. The most effective CFOs understand this deeply. They do not relegate systems integration to information technology or operations alone. They treat it as a strategic weapon. Because if used wisely, the process of integration forces an organization to clarify what matters, simplify what does not, and rebuild how it operates with first-principles logic.

When Integration Becomes Friction

Let me illustrate with an example I witnessed. A growth-stage company acquired a smaller but highly innovative competitor. The logic was clear: same market, complementary product, cultural fit. The combined customer base would allow immediate cross-sell opportunities. On paper, it was a home run. But six months post-close, sales efficiency was deteriorating. Churn ticked up. Product releases slowed. Engineering attrition spiked. Instead of unlocking synergies, the company found itself managing friction. Everyone was polite. But no one was aligned.

The issue was not culture or strategy. It was systems. Salespeople did not know which pipeline rules applied. Customer success had two playbooks and no authority to unify them. Engineers spent more time reconciling project management boards than shipping code. The enterprise resource planning migration had been deferred for cost reasons, so reporting cycles took twice as long and were half as useful. The executive team, for all their intent, found themselves buried in reconciliation work instead of looking forward.

This is what happens when integration is viewed as a tactical necessity rather than a strategic inflection point. During my time leading mergers and acquisitions activity including a one hundred million dollar acquisition integration for a multi-studio gaming enterprise, I learned that the lesson is consistent: post-merger systems integration is not about combining platforms. It is about deciding, with precision and courage, what kind of company you are now becoming.

The Strategic Choices Embedded in Systems

Do you lead with sales or with product? Do you optimize for speed or for control? Do you prioritize accuracy or agility? These are philosophical choices. But they manifest operationally in fields, workflows, permissions, and reports. They show up in how quickly you invoice, how reliably you forecast, and how confidently your employees move through a merged environment. If you do not make these choices deliberately, the organization will default to the path of least resistance. You will inherit the worst of both worlds.

Some will argue that all integrations are messy. They are right. But messiness is not the enemy. Indecision is. The companies that use integration as a strategic weapon do several things differently.

First, they begin with a systems thesis. They define up front what the combined enterprise should be able to do better, faster, or smarter than before. This might be better cohort tracking, tighter inventory turns, more accurate customer acquisition cost attribution, or unified net promoter score tracking. Whatever it is, they tie systems integration to key strategic outcomes. Having designed enterprise key performance indicator frameworks using business intelligence tools like MicroStrategy and Domo for tracking bookings, utilization, backlog, annual recurring revenue, pipeline health, and customer margin, I know that these frameworks only work when systems are designed to support them.

Second, they put finance at the table early. Not just to model costs, but to design the operating model. Most systems decisions are ultimately financial decisions. Whether you keep two payroll systems running in parallel for six months or consolidate in two weeks is a cost-benefit call. Whether you rebuild your revenue recognition policy to reflect the acquired business model is a governance choice. When I led the design of multi-entity global finance architecture spanning operations across the United States, India, and Nepal, the success depended on getting these foundational decisions right. If finance waits to get involved until go-live, the damage is already done.

Third, they treat systems not as tools, but as behavioral frameworks. You cannot tell sales teams to unify unless they trust the customer relationship management system to reflect reality. You cannot expect financial planning and analysis teams to model synergies if the source data is inconsistent. You cannot claim integration is complete when your onboarding flows diverge and your revenue definitions vary by business unit. In my experience implementing ASC 606 revenue recognition and automating revenue operations across professional services and software as a service businesses, the technical implementation was only half the challenge. The other half was ensuring teams understood and trusted the new processes.

Fourth, and perhaps most critically, they allocate integration capital wisely. It is easy to overspend on low-value migration and underspend on enablement. Moving data is not the hard part. Teaching people how to use it, trust it, and act on it is. A CFO who sees integration as strategy will invest more in change management than in system migration and will be proven right.

Simplification as Strategic Outcome

The best integrations I have witnessed all shared one feature. They simplified the business. Not in a superficial way. Not by deleting features or departments. But by eliminating duplicative logic, removing procedural noise, and giving every team a shared view of truth. This mirrors my experience improving month-end close processes from seventeen days to under six days. The breakthrough was not automation alone. It was eliminating unnecessary complexity and establishing clear ownership and accountability.

Let me offer another example. A large enterprise acquired a mid-market software as a service company and planned to sunset the acquired billing system in favor of its own. The acquired company, however, had an elegant usage-based pricing model, while the parent company relied on traditional seat-based billing. Instead of forcing the smaller company onto its platform, the CFO paused the integration and asked a fundamental question: which billing model better reflects where the market is going?

The answer was clear. Usage-based pricing, while more complex, was better aligned with customer value and offered stronger expansion potential. So rather than integrate the smaller firm into the old system, the company chose to rebuild its own billing engine from scratch, using the acquired platform as a blueprint. It took nine months. It cost more than expected. But within two years, the entire enterprise shifted to usage-based pricing, drove higher net revenue retention, and built a new data architecture that allowed finance to forecast with unprecedented precision. The acquisition became a strategic fulcrum not because of its customers, but because of its systems. That is what I mean by using integration as a weapon.

The Questions That Matter

Not every deal warrants such depth. But even modest acquisitions can benefit from principled systems thinking. At a minimum, ask yourself these questions: What truth does each system protect? What decisions does each system enable? What assumptions are embedded in how each process works? What friction will arise if we layer one set of workflows on top of another? And most importantly, what outcome will we not be able to achieve unless we redesign how we operate?

These are not information technology questions. They are strategic questions. And the CFO is uniquely positioned to ask them. My background spanning certifications in accounting, management accounting, internal audit, production and inventory management, and project management has taught me that these disciplines converge in systems integration. You need the rigor of an auditor, the strategic thinking of a CFO, the process discipline of a project manager, and the operational insight of an inventory planner.

Integration as Leadership Test

Ultimately, post-merger integration is not a project. It is a test of leadership. It is a moment where everything is on the table, where legacy habits can be challenged, and where a new system of operating can be built not just to serve the finance team but to serve the mission. That mission, whether it is growth, efficiency, innovation, or resilience, will be accelerated or inhibited by the quality of integration. It will show up in margins, in speed, in employee trust, in board confidence, in market responsiveness.

Having managed board reporting and created investor-grade financial models across organizations raising over one hundred twenty million dollars in capital, I know that boards evaluate integration quality through these outcomes. The metrics tell the story of whether integration succeeded or failed.

The next time your company closes a deal, do not let the press release be the peak of your effort. Treat day one as the starting line for the harder, more meaningful work. Convene your teams. Map your processes. Challenge your defaults. Allocate time, not just budget, to getting the integration right. And most of all, be willing to use the integration to do something bold: retire broken processes, reimagine how teams collaborate, rebuild truth from first principles.

Conclusion

In a world of accelerating change, it is not the merger that delivers strategic advantage. It is what you do with it. The most powerful weapon in that arsenal is not capital. It is clarity. Clarity, powered by systems that work, teams that trust those systems, and leadership that sees integration not as a burden, but as a once-in-a-decade opportunity to get better.

So when technology meets process, meet it with intent. That is where transformation hides. And that is where strategic advantage is forged, not in the pitch deck, not in the term sheet, but in the quiet, deliberate decisions that turn two companies into one. Let others chase headlines. Let your integration speak through results.

Disclaimer: This blog is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax advisor or counsel for advice tailored to your specific situation.

Hindol Datta is a seasoned finance executive with over 25 years of leadership experience across SaaS, cybersecurity, logistics, and digital marketing industries. He has served as CFO and VP of Finance in both public and private companies, leading $120M+ in fundraising and $150M+ in M&A transactions while driving predictive analytics and ERP transformations. Known for blending strategic foresight with operational discipline, he builds high-performing global finance organizations that enable scalable growth and data-driven decision-making.

AI-assisted insights, supplemented by 25 years of finance leadership experience.